Technote: Bell P-39, Inventor FaceDraft

Draft angles is actually a common requirement when working with aircraft components, particularly forgings, and it is surprising that I haven’t written an article on this before now.

Facedraft in Inventor is a feature that allows adjusting the face or faces of an object to a specified angle. A more detailed overview is described in this Autodesk article Face Draft feature

Occasionally the implementation is not quite so straightforward as noted therein and some outside the box thinking is necessary. Thus was the case when I was building the forging component for the P-39 Landing Gear Nosewheel Scissor.

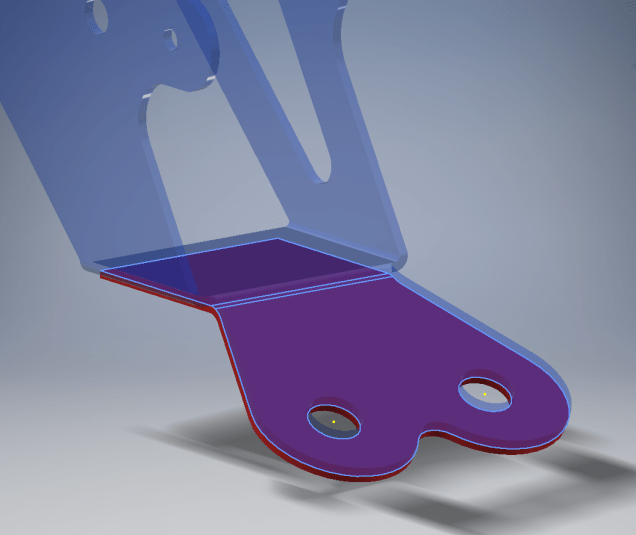

To build this component I created 2 separate solid bodies, one for the cylinder item and one for the fork. The fork is split about the X,Y plane with only the outline of the top half being modeled to facilitate the initial face draft.

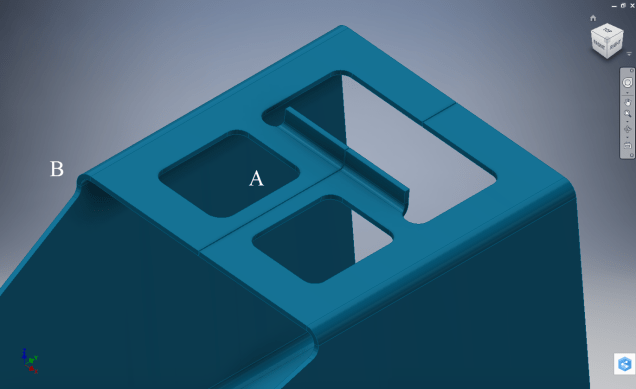

For the first option, I selected the X,Y plane and then for the Faces I selected the automatic face chain option and placed the cursor close to the top edge as shown. If you required the face angle to originate from the bottom edge then you would select the faces close to this edge.

I then trimmed out the inside profile of the fork and applied a face draft as above.

Now it was only a matter of mirroring the fork solid to complete this portion. Notice the solids are still separate items which will be combined as one after inclusion of the central web component.

There is an option for the Facedraft feature to Draft using a parting line, either a 2d or 3d sketch. The draft is normally applied above and below this parting line. In most circumstances, the Parting Line option works well but occasionally the model may be too complex to achieve the desired result thus the solution described here provides an alternative approach.

Forgings or castings commonly have a draft angle on all faces which is normally 7 degrees and occasionally 5 degrees. The Face Draft feature is ideal for applying the drafts with an extensive range of options. The model of the forging would then be derived into a separate part file and then machined according to the finishing requirements similar to the process described here Derived Parts.

For more information on the Bell P-39 Airacobra project: Bell P-39: Project

102-00005: Fuselage (BC main)

102-00005: Fuselage (BC main)