1. Use names in lieu of cell addresses

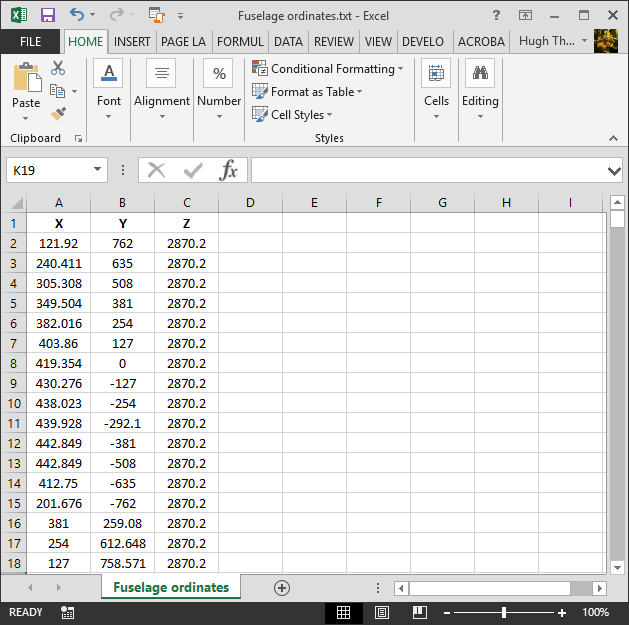

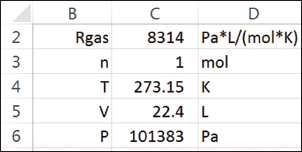

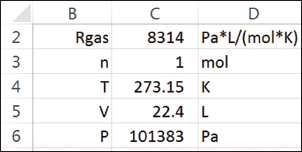

Consider the ideal gas law (Wikipedia) calculation in the Excel spreadsheet in Figure 1.

▲Figure 1. For easy readability, this ideal gas law calculation has labels in the left column, values in the center column, and units in the right column.

Contrast the following formulas for calculating the value in cell C6:

Although this is a simple example, the advantage of the formula on the right is evident. In order to reverse-engineer formulas that use cell addresses, such as the one on the left, you would have to trace back the source of each quantity. The formula on the right uses cell names that relate to the variable names from the familiar algebraic ideal gas equation. The style of the spreadsheet layout also improves readability. In Figure 1, the labels in column B are the same as the names for the cells in column C.

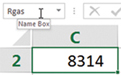

There are three common ways to create names for cells. A convenient method is to select the cell, and type the name into the Name Box field above the column A label:

You can also transfer the label from an adjacent cell onto the cell of interest using Create from Selection in the Defined Names group on the Formula tab of the Ribbon (Figure 2). In fact, more than one label can be transferred with a single command.

▲Figure 2. Create names for cells using the Create from Selection command.

Use the Name Manager in the same Defined Names group to create, edit, and delete names. Cell names generally have global scope in the workbook, but it is possible, using the Name Manager, to create names that have scope only in the worksheet where they are created.

Note that certain names are not allowed. First, you cannot create a name that is the same as a cell address. Given the size of the modern worksheet (the Excel spreadsheet has 214= 16,384 columns and 220 = 1,048,576 rows — a total of 234 cells), with columns out to XFD, it is easy to confuse a name with a cell address. Second, you cannot use the letters R or C as names or those letters followed by any digits. This restriction harkens back to the R-C method of cell addressing (i.e., row-column), which is rarely used today.

The following shows an example of practical formulae using named cells.

2. Set up calculations in their natural sequence and targeting methods.

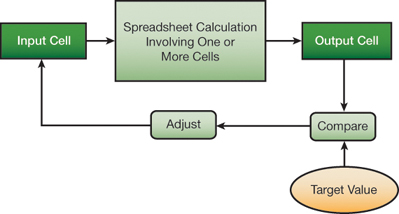

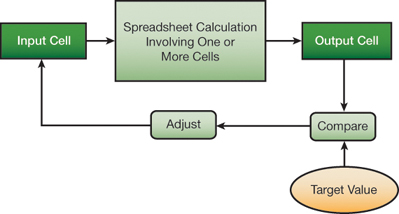

It has been said before many times to start at the beginning and finish at the end. For most engineering problems, there is a natural sequence that starts with basic data and proceeds step-by-step to a final result. However, in many calculations, you may need to find one or more starting values that yield a desired final result, or a target value (Figure 3). The target may be a specific value, or it could be the minimum or maximum of a function, such as cost or profitability. The calculation may have more than one input cell, and there may be constraints on various elements of the calculation.

▲Figure 3. Targeting methods, such as Goal Seek or Solver, can help you determine the input value that yields a desired output or target value.

For one-time solutions of these targeting problems, you can often simply adjust the input value by trial-and-error and meet the target after only a few tries. Excel offers two tools that automate this procedure: Goal Seek and Solver. (The Solver is an add-in provided by Frontline Systems. For information and guidance on using the Solver, see

www.solver.com.)

Excel’s Goal Seek is only able to solve target value problems. It is a black-box tool that does not give the user options or control over its numerical procedure. For example, we want to determine the liquid depth in a 4m-diameter spherical tank that corresponds to a volume of 10 m3. The formula is:

where V is the volume, h is the liquid depth in the tank, and Rd is the radius of the tank. We set up a calculation on the spreadsheet based on a test value of 2 m for the depth (Figure 4a-b).

▲Figure 4. The total volume of a liquid in a tank is calculated for an arbitrary liquid height of 2 m (a) by the formulas shown in (b). Use Goal Seek to set the volume equal to 10 m3 by changing cell h (c) to find the depth corresponding to a 10-m3 volume (d).

Invoke Goal Seek from the What-If Analysis drop-down list in the Data Tools group of the Data tab of the Ribbon. Complete its fields, as shown in Figure 4c, by setting cell V equal to 10 m3 by changing cell h. Upon clicking the OK button and accepting the result, we have the solution that h = 1.45 m (Figure 4d).

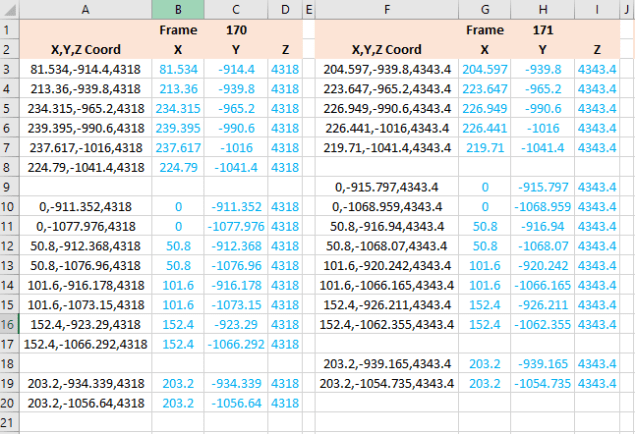

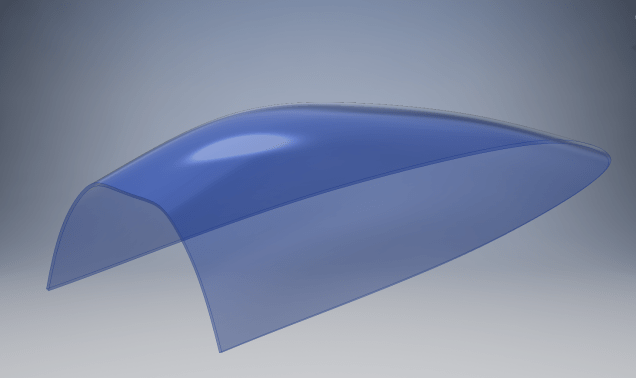

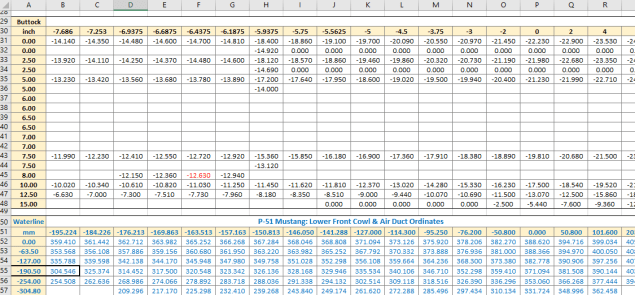

For use in Cad systems like Autocad, it is recommended to collate these in a TXT file by simply copying and pasting.

For use in Cad systems like Autocad, it is recommended to collate these in a TXT file by simply copying and pasting.