Technote: Sheetmetal; Avoid Bend Stress Points:

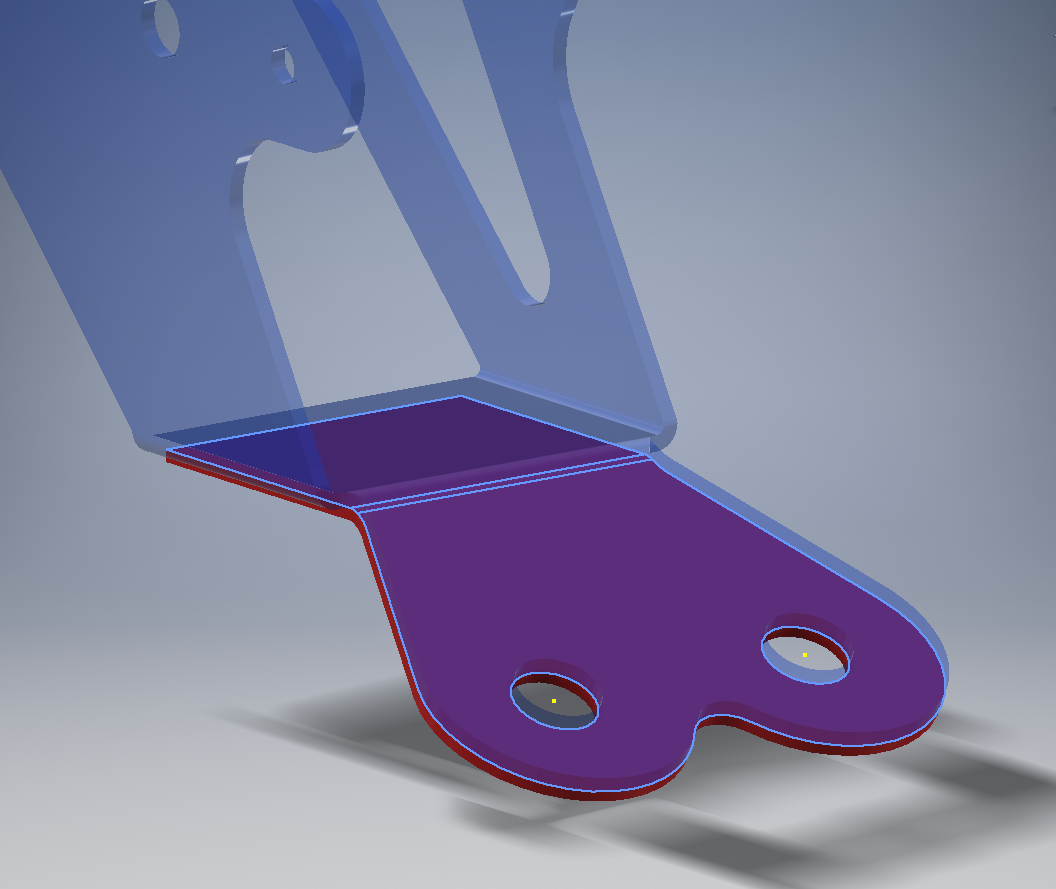

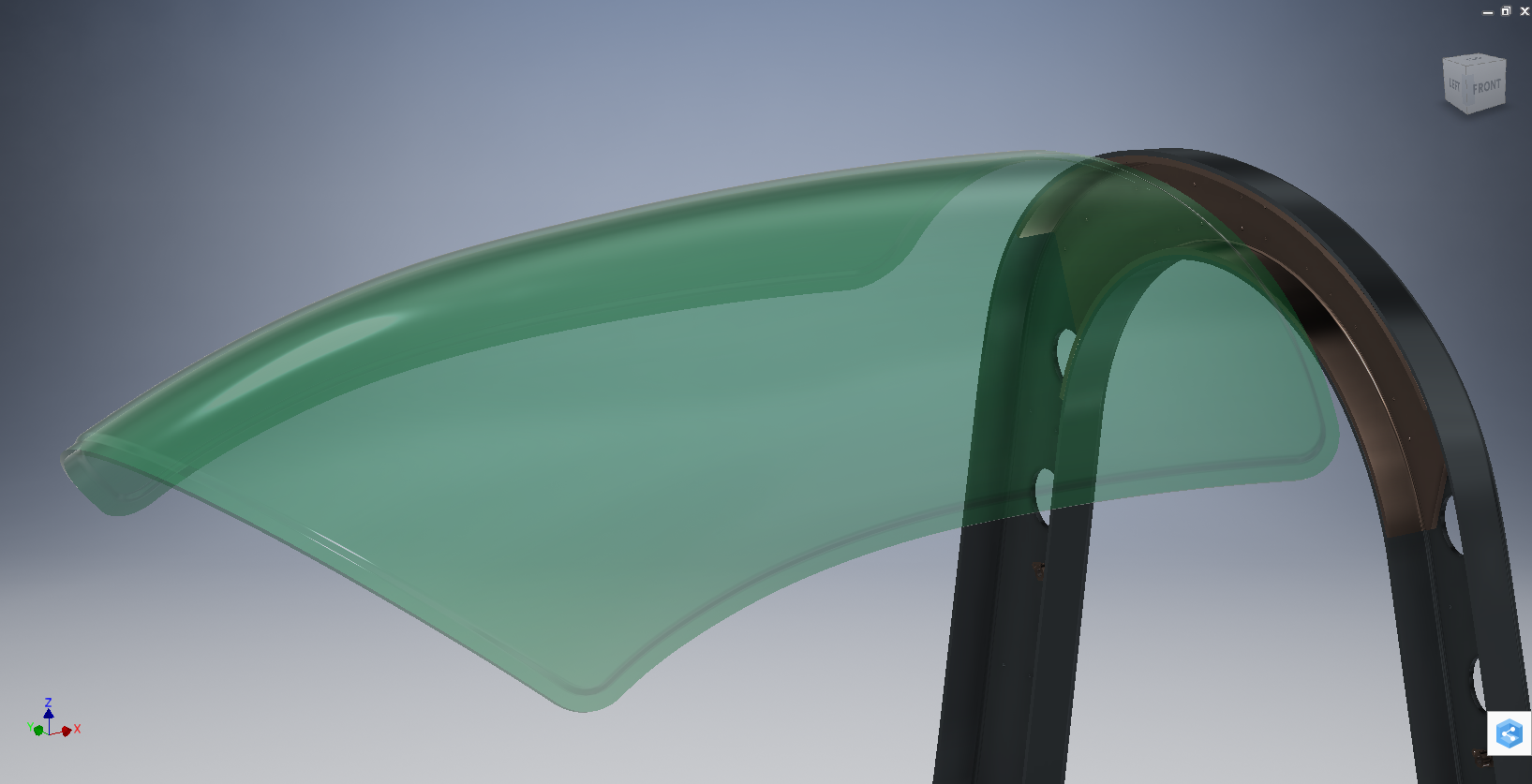

This is a sheet metal part for the P-39 Airacobra (#12-509-052) sent to me by a fellow enthusiast for comment. Before I get immersed in discussion on this subject I would just say that this part is a cable cover that is unlikely to be under any substantial stress and thus would probably be fine as modelled.

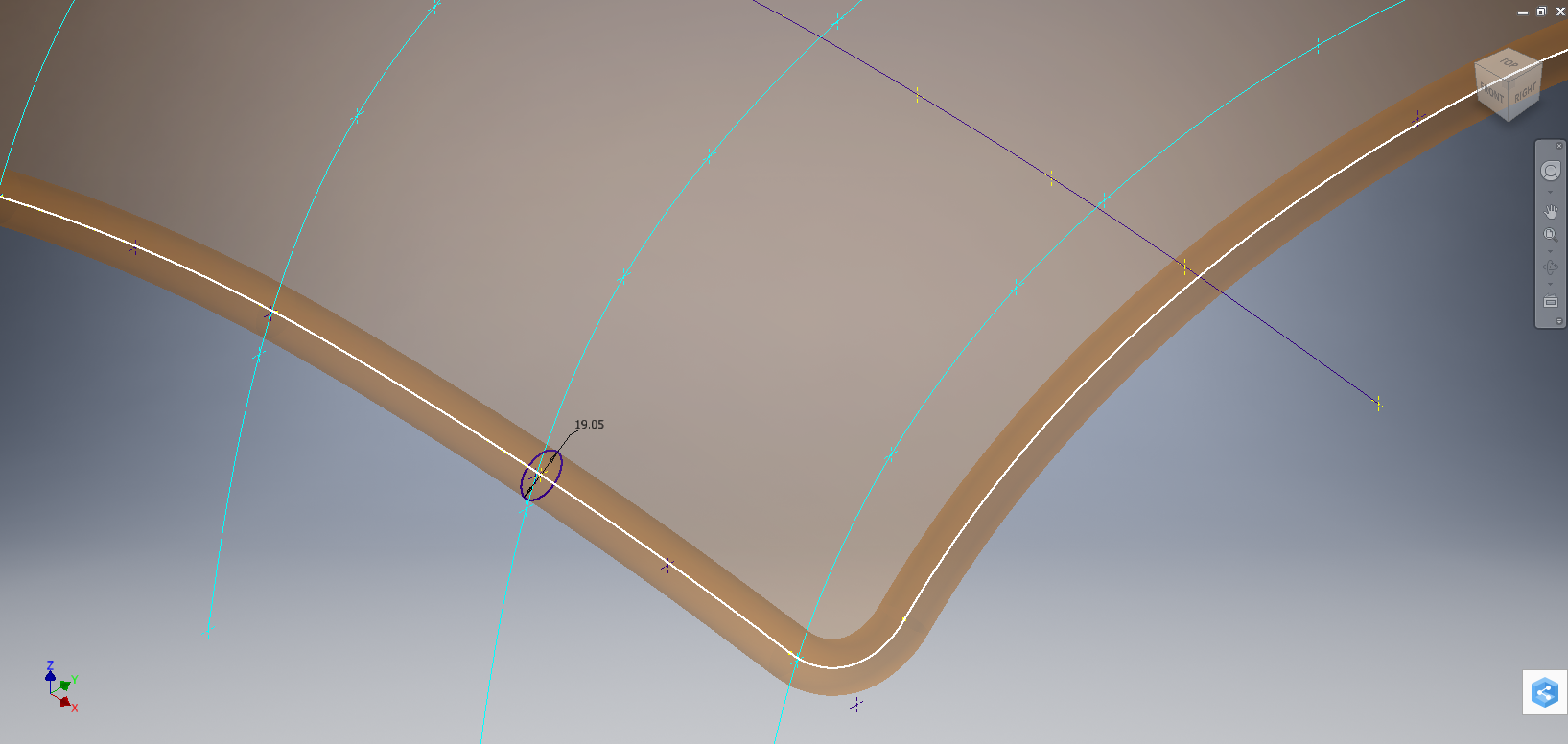

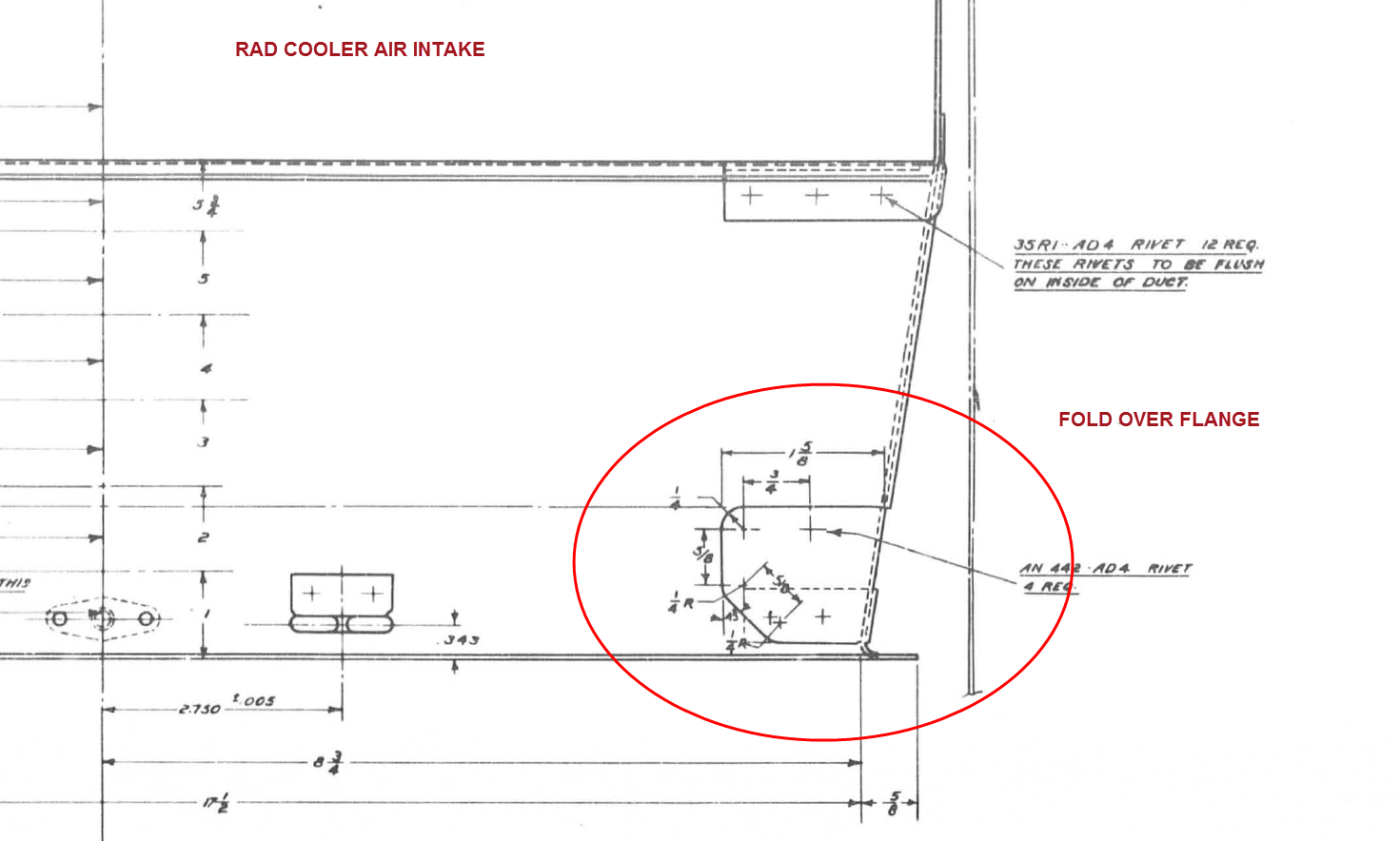

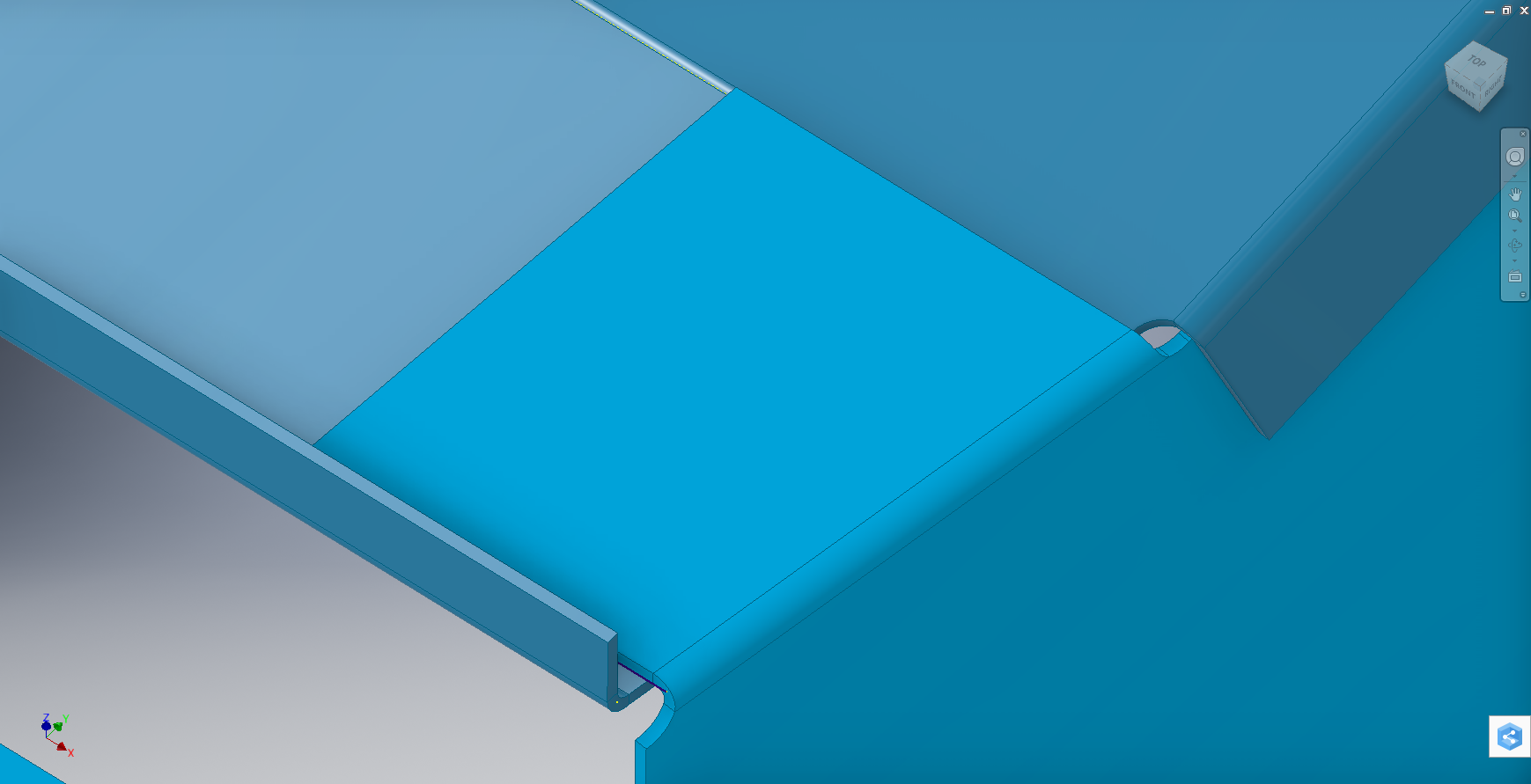

The part comprises 2 tabs, one on the top and one on the bottom. It is the fillet radius that I will focus on. The first bend is offset from the edge of the plate. The drawing specifies a 5/32″ (4mm) radius for the fillets at the intersection of the top tab and the main body which overlaps the sheet metal bend. The originator has taken this literally and attempted to create a finished fillet of 5/32″.

I suspect that the drawing is actually referring to a 5/32″ radius as it would be for the developed flat pattern because doing so otherwise; due to the bend being offset as illustrated on the cad model; this introduces stress points.

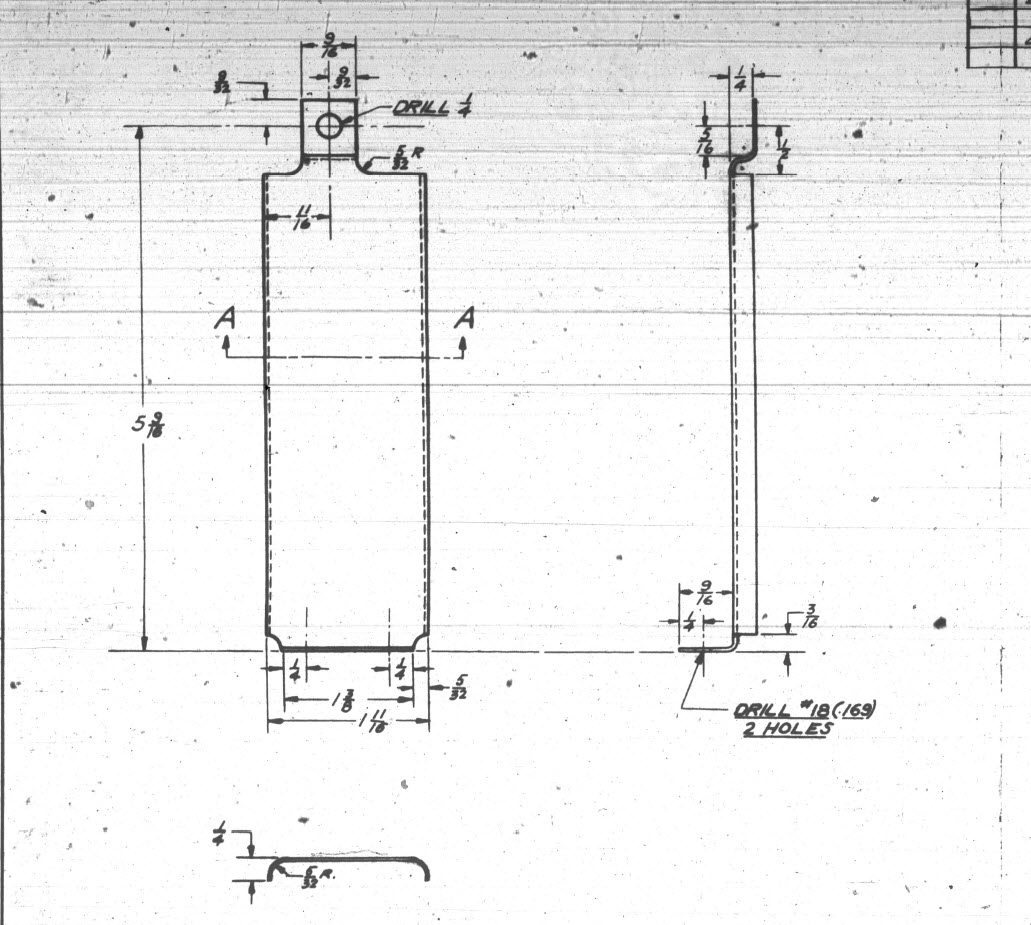

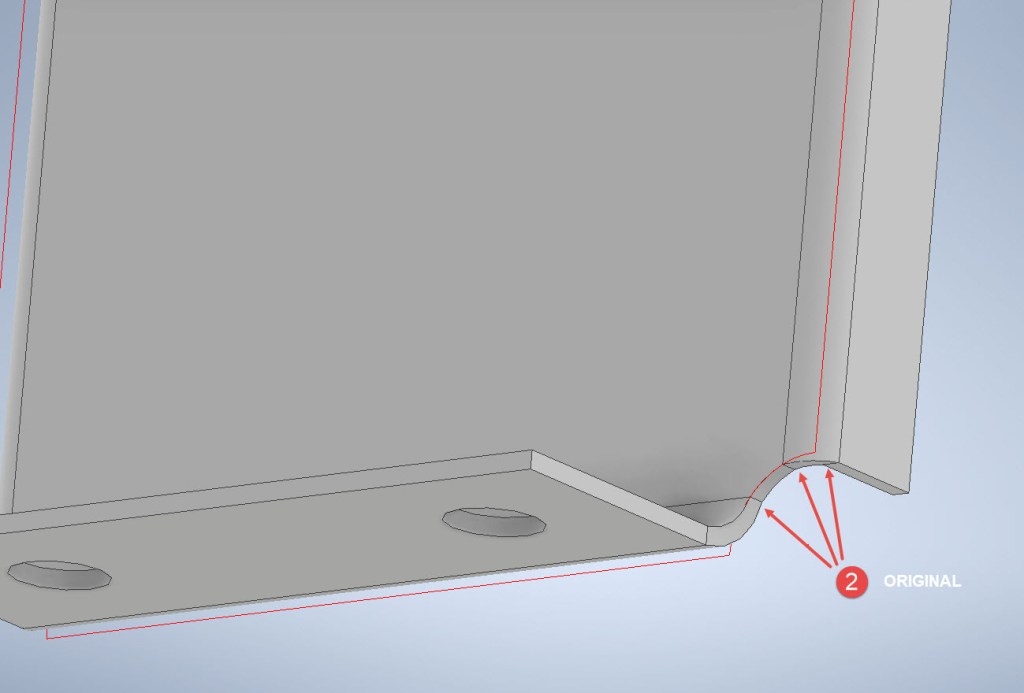

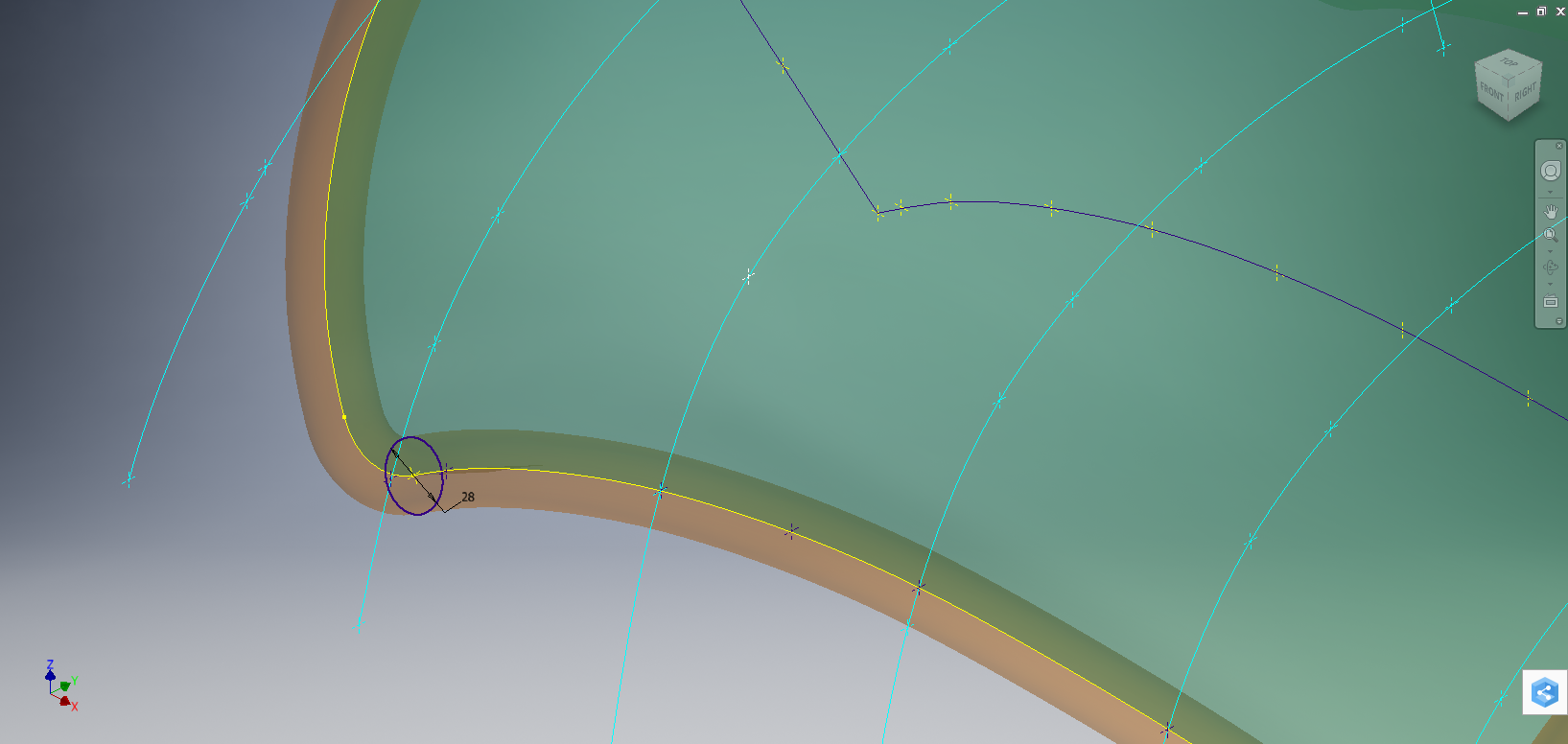

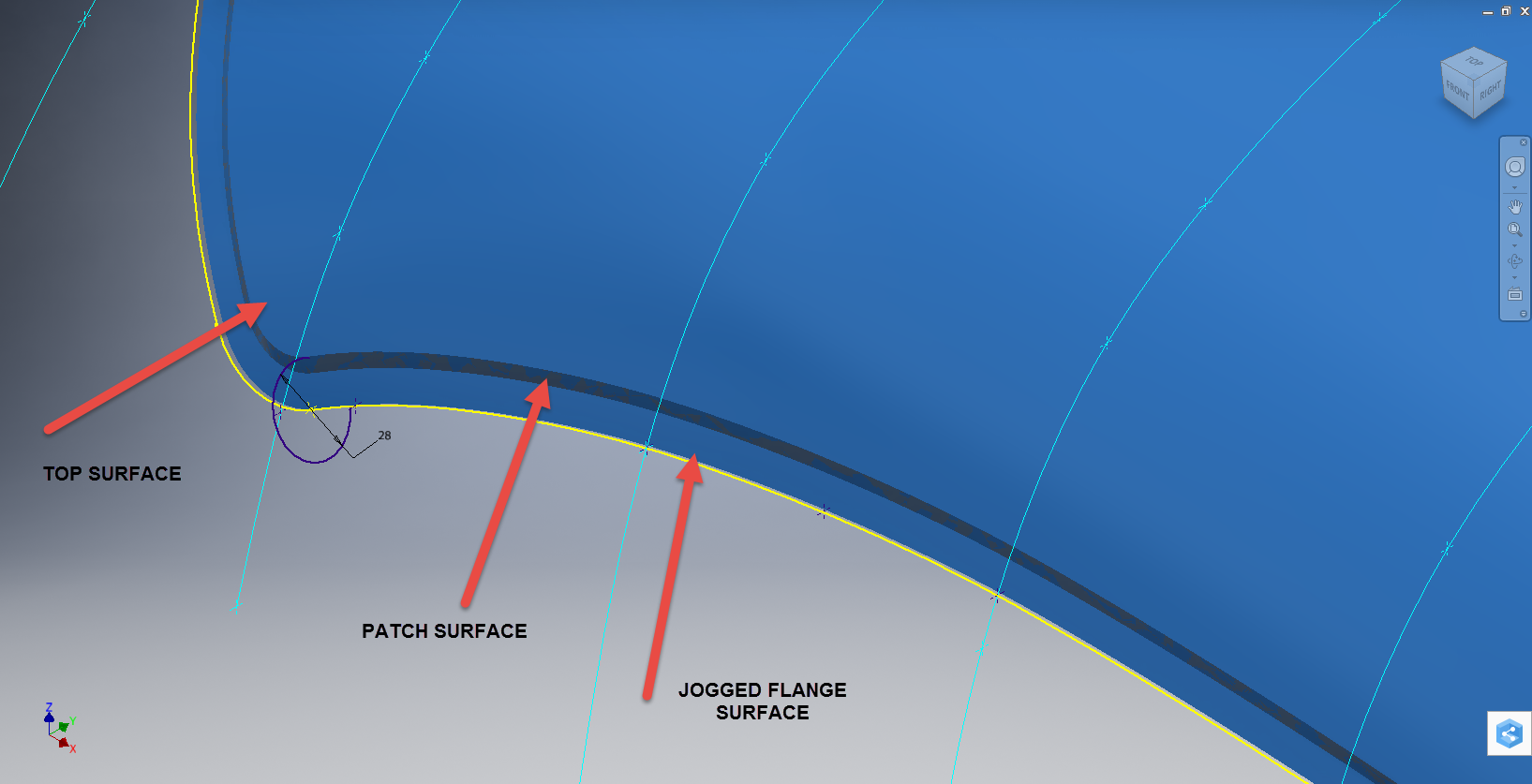

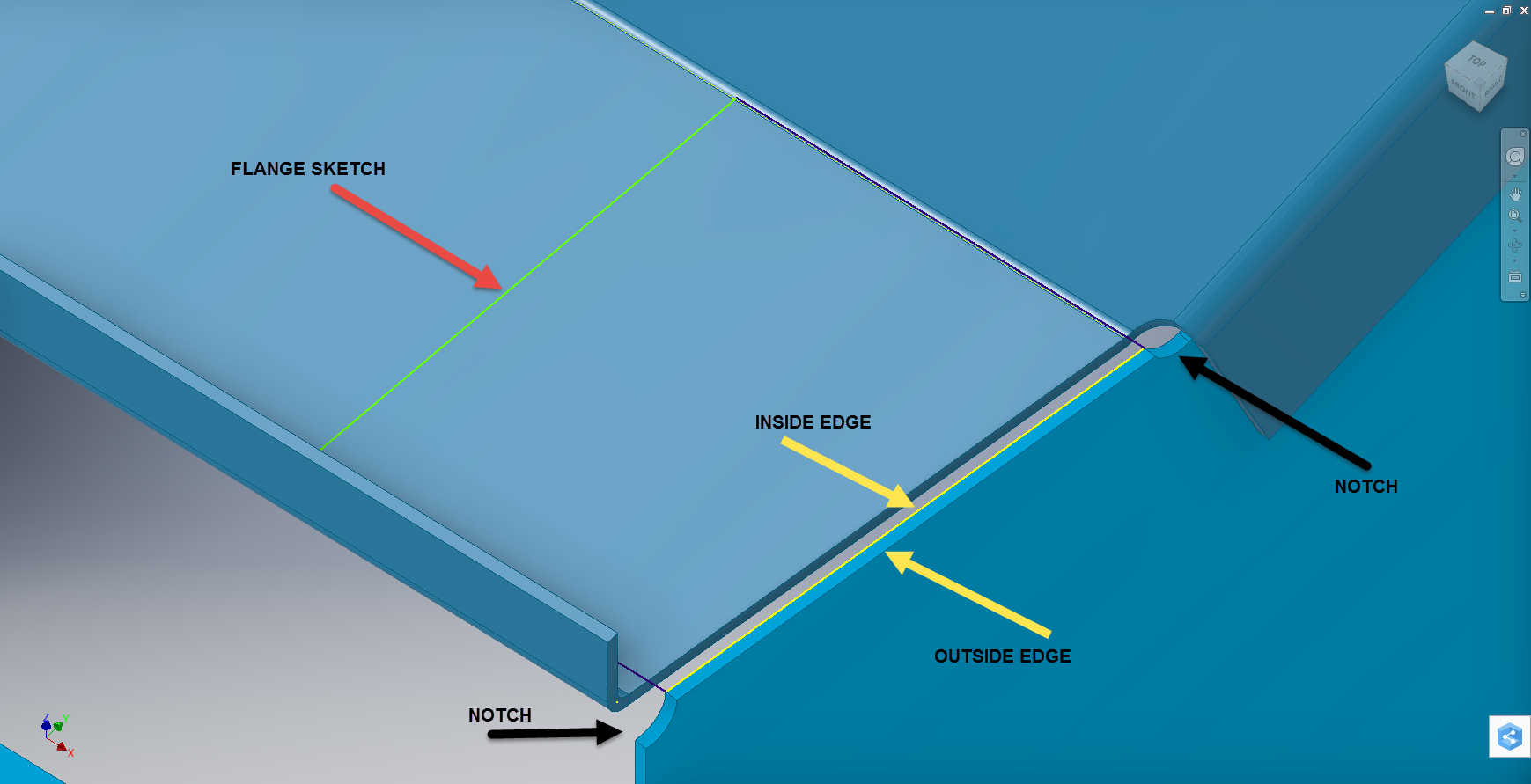

The images show the irregular continuity which creates angular edges that essentially become focussed stress points. It is often best to try to achieve smooth continuity both for bending purposes and of course when in use. What they did was sketch a face profile; which included the specified radius (#1)and then proceeded to adopt the standard commands to build the flanges. Technically it is not wrong but as the manufacturer’s drawing does not contain a developed flat pattern it is often misinterpreted…the radius should perhaps be applied to the pattern before bending.

Similarly, at the bottom tab, we also have irregular continuity as shown at #2.

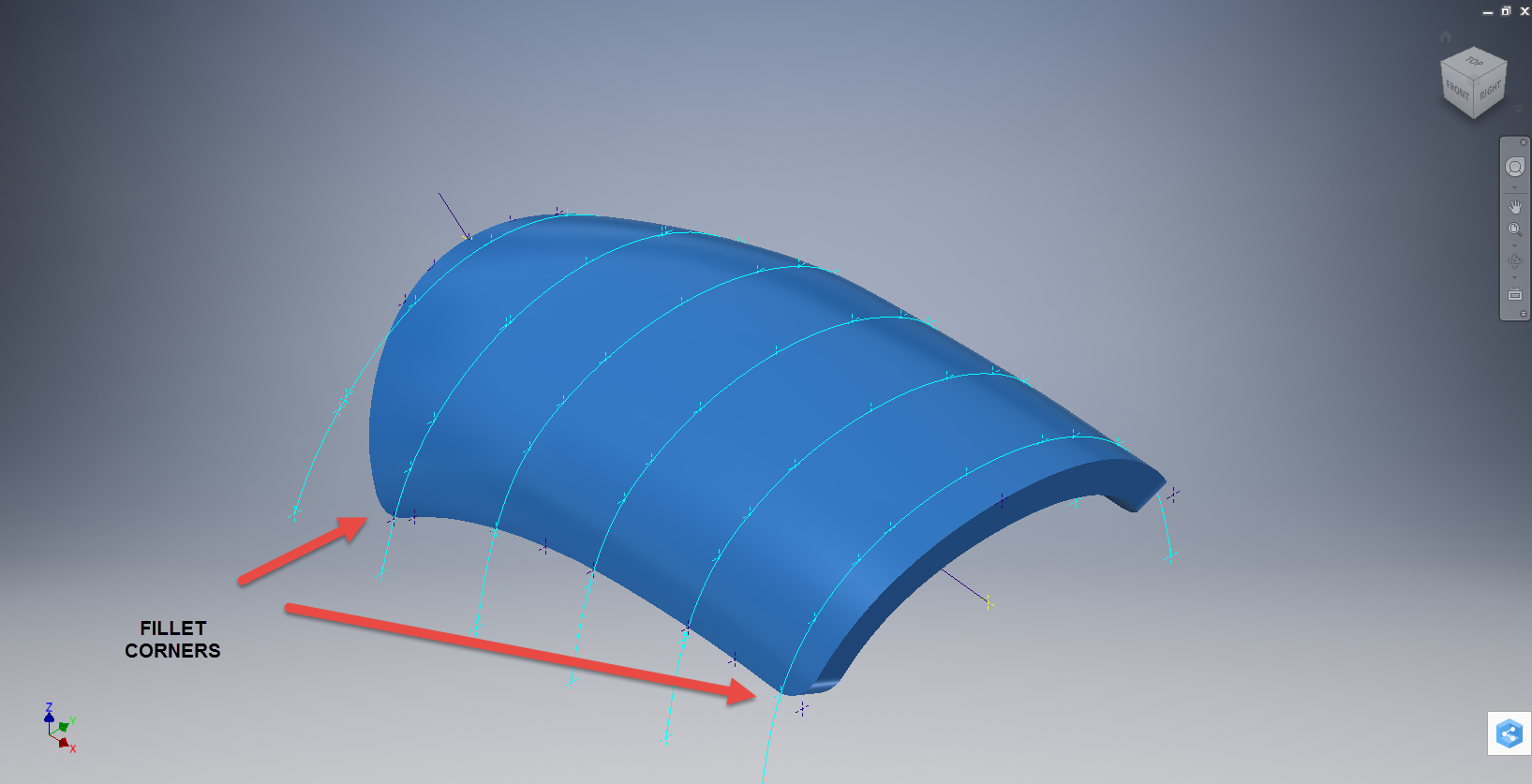

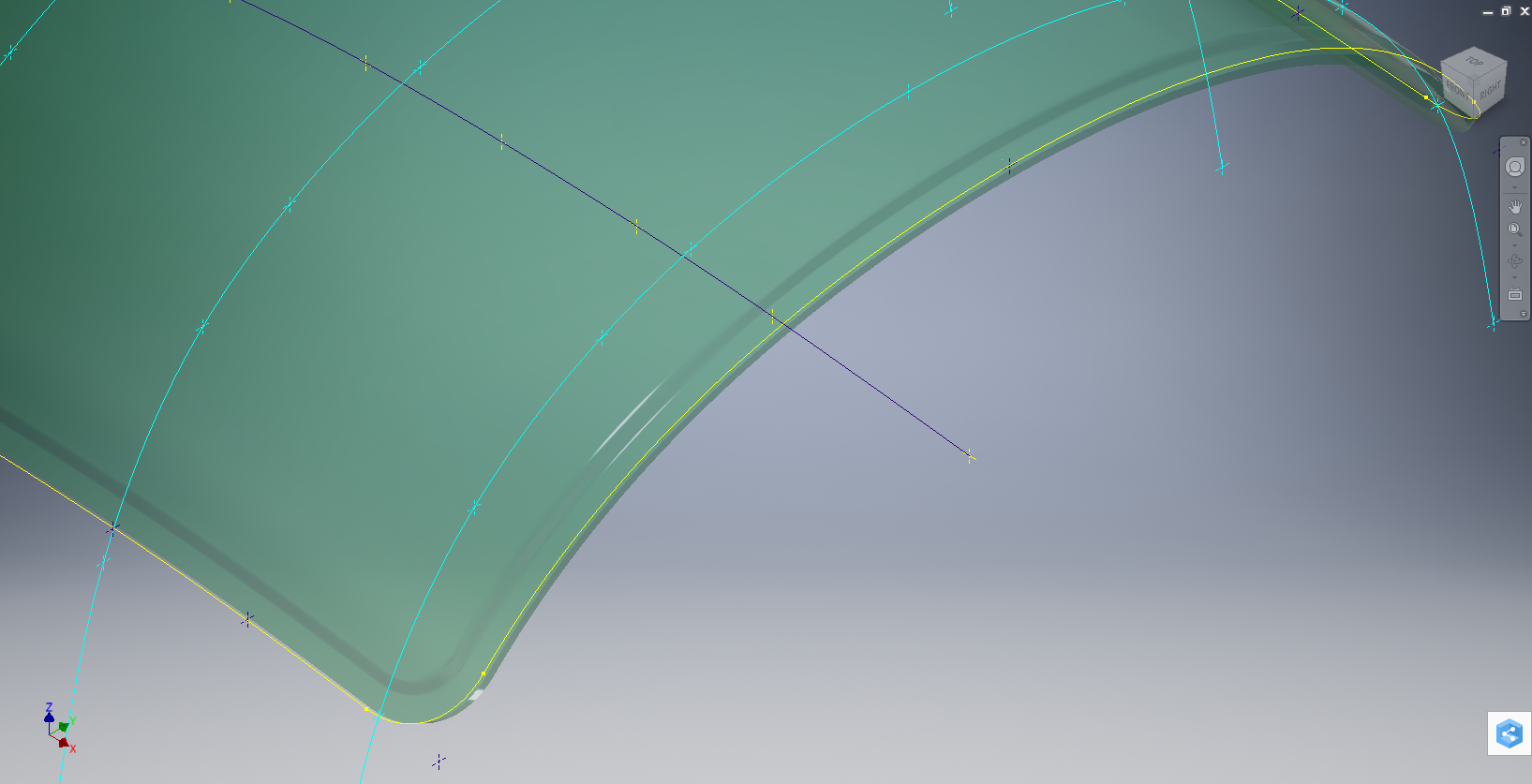

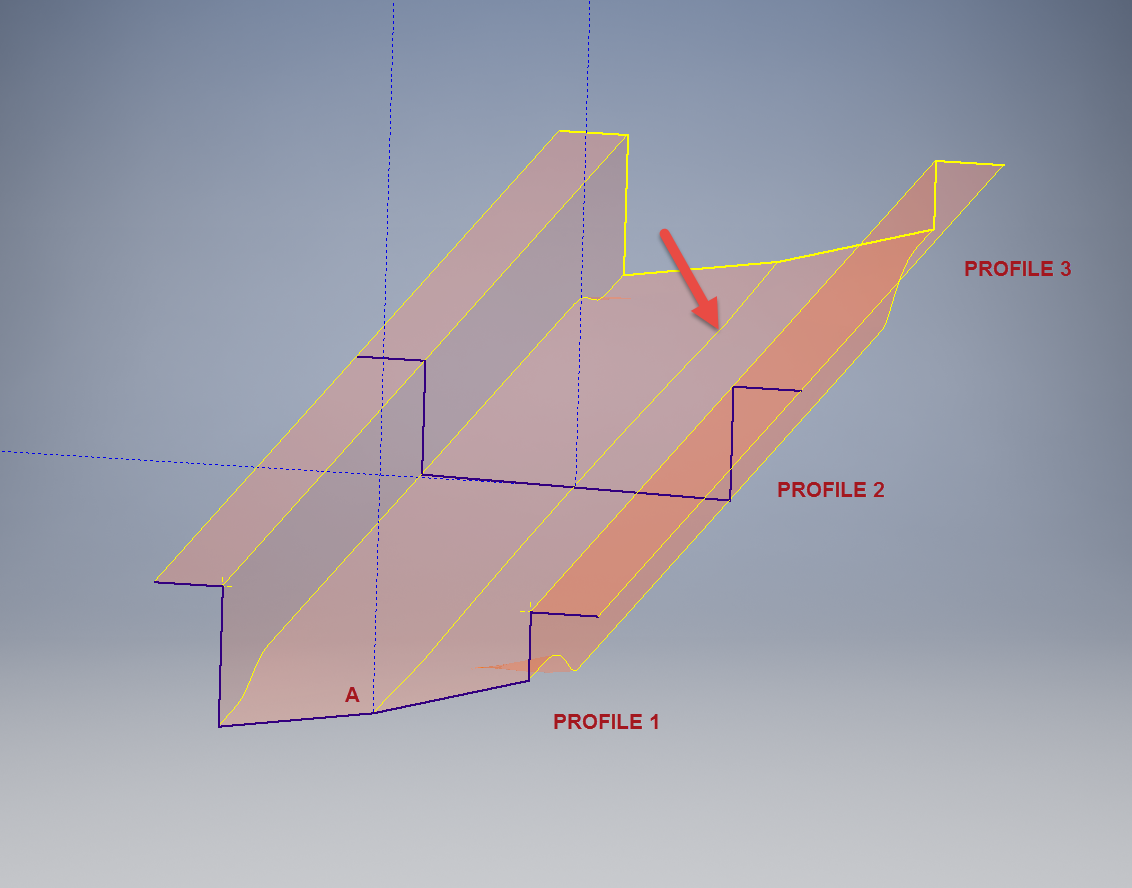

I rebuilt this model to address these issues and you can see how a small change in modelling technique can obviate some of these issues.

The images show the developed pattern with the original cad model on the top and the new version on the bottom. At #3 the outline of the tab would be difficult to cut with the small taper before the fillet, whereas the lower profile at #4 is easier to cut with no stress points. Similarly for the base tab at #5 and #6. I should note that the bottom tab radius is not specified so I opted for the default minimum which fits nicely before the bend lines.

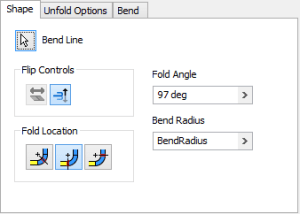

There are several ways to do this with the easiest being accomplished by using the Unfold command on a square flange and then applying the fillet before refolding. The option I have used here is first to draw an extended flange as part of the initial face sketch, create the first part of the model as a Face then apply the 5/32″ fillet before bending along a predetermined bend line sketch.

The sketched tab outline is a lot bigger than is required which of course can be trimmed once the tab is complete. You can see the extents of the tab on the initial sketch…you only need to add a plane at that point to trim. The resulting fillet is a smooth continuity with no obvious stress points.

Understandably the designers wished to increase the amount of material at the bend to maximise strength so it is advised to try to achieve those goals. As I said before, for a cover like this it is probably not too critical if we only applied a small fillet but for framing and structural elements, it may be critical.

One quick note on the 2 vertical flanges…the drawing specified an internal radius of 5/32″ which to be honest is unworkable as the resulting bend would overlap the bottom tab…in this case, I opted for the minimum specified.

At the end of the day, it is down to the interpretation of the designer intent. For the majority of sheet-metal drawings, they often do not include developed flat patterns but may contain information that is actually applicable to the flat pattern and not necessarily the finished folded profile.

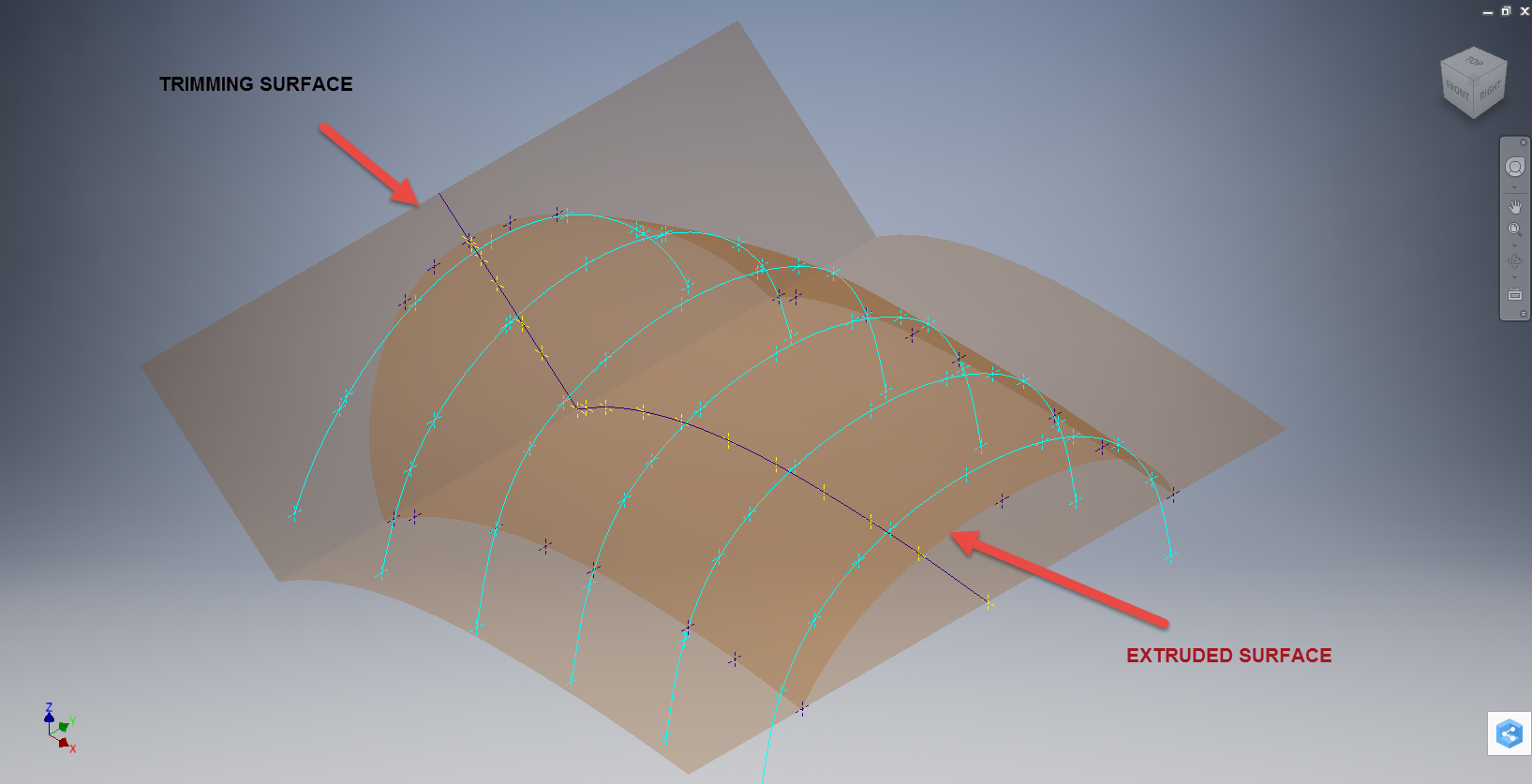

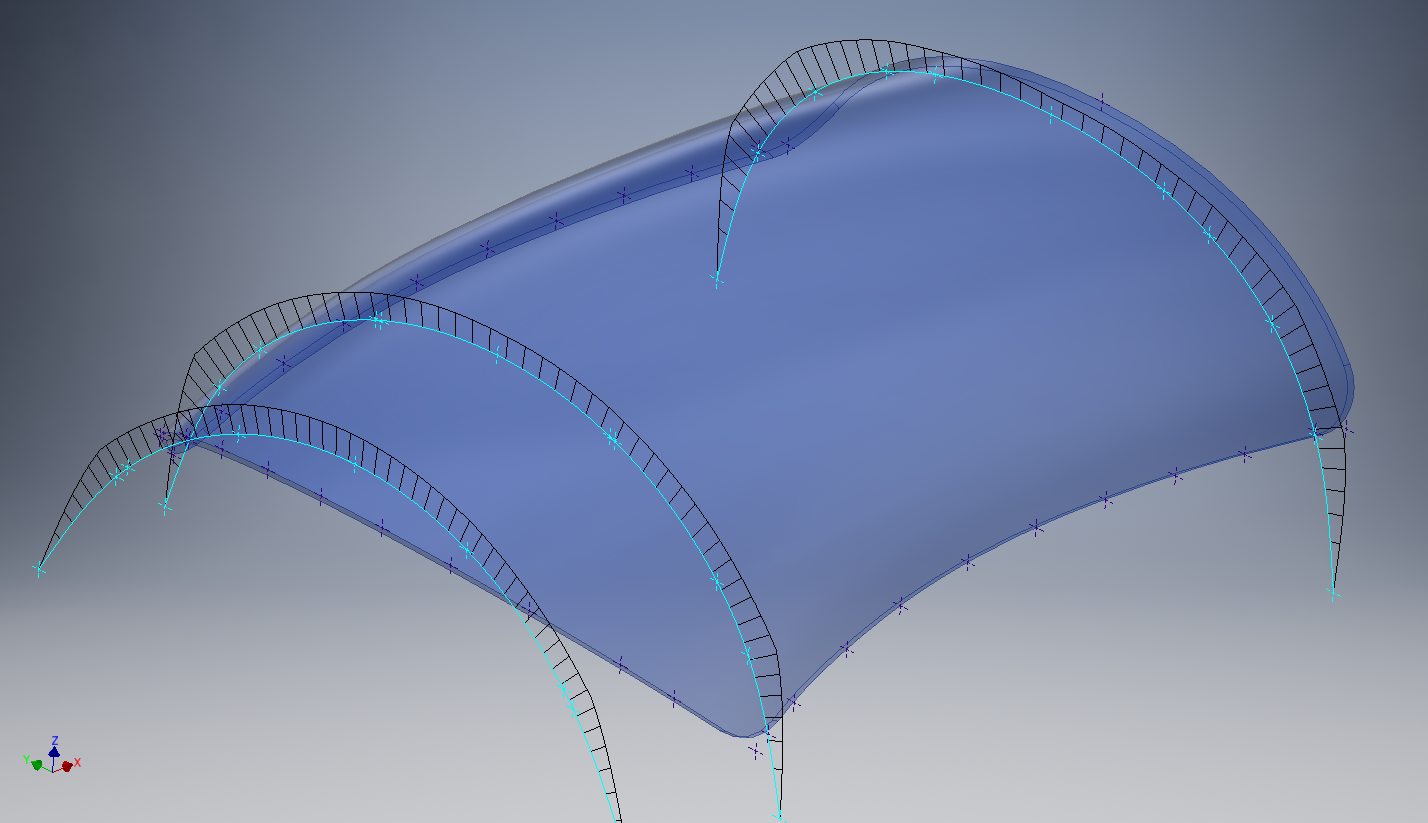

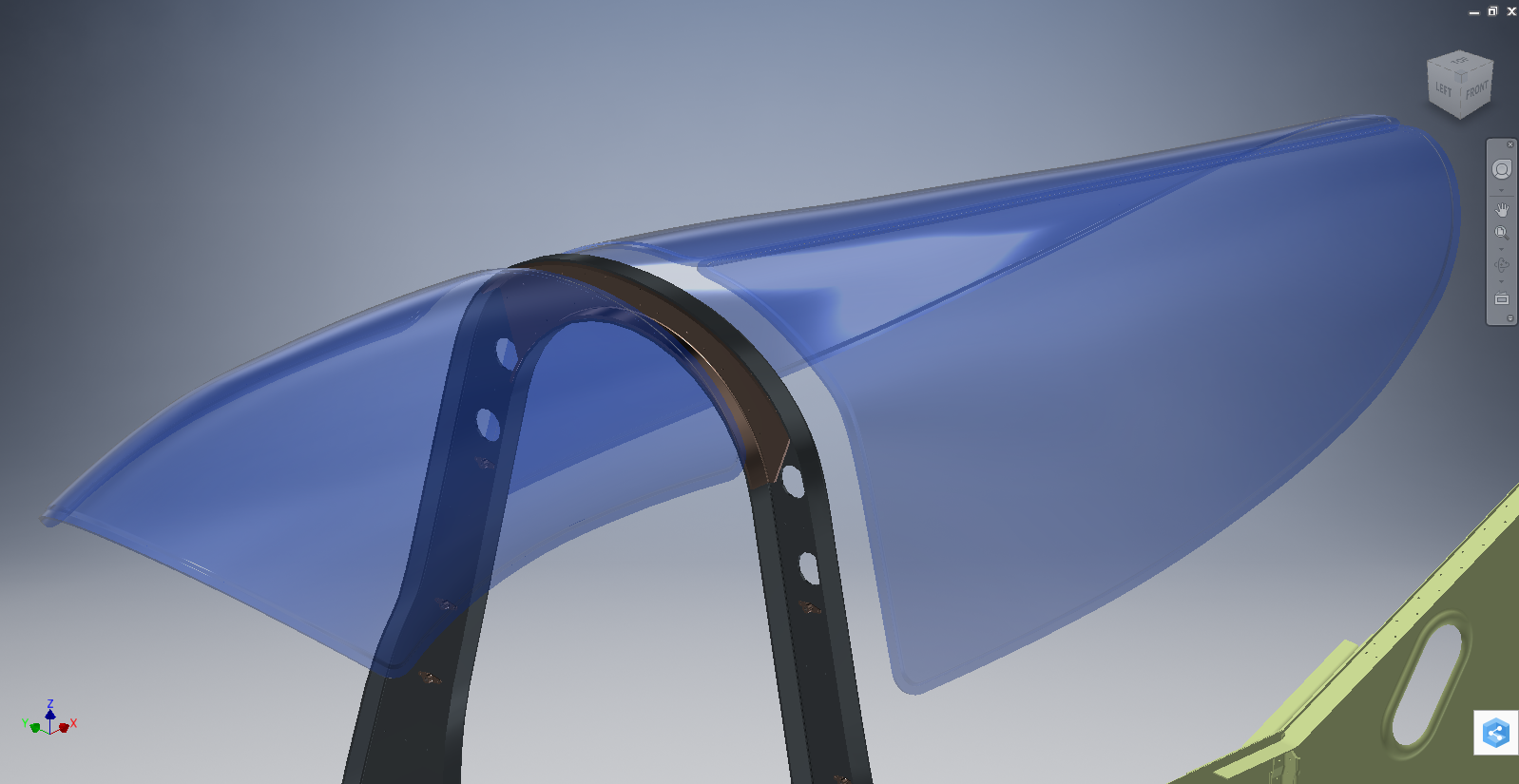

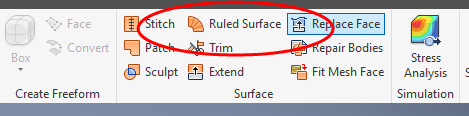

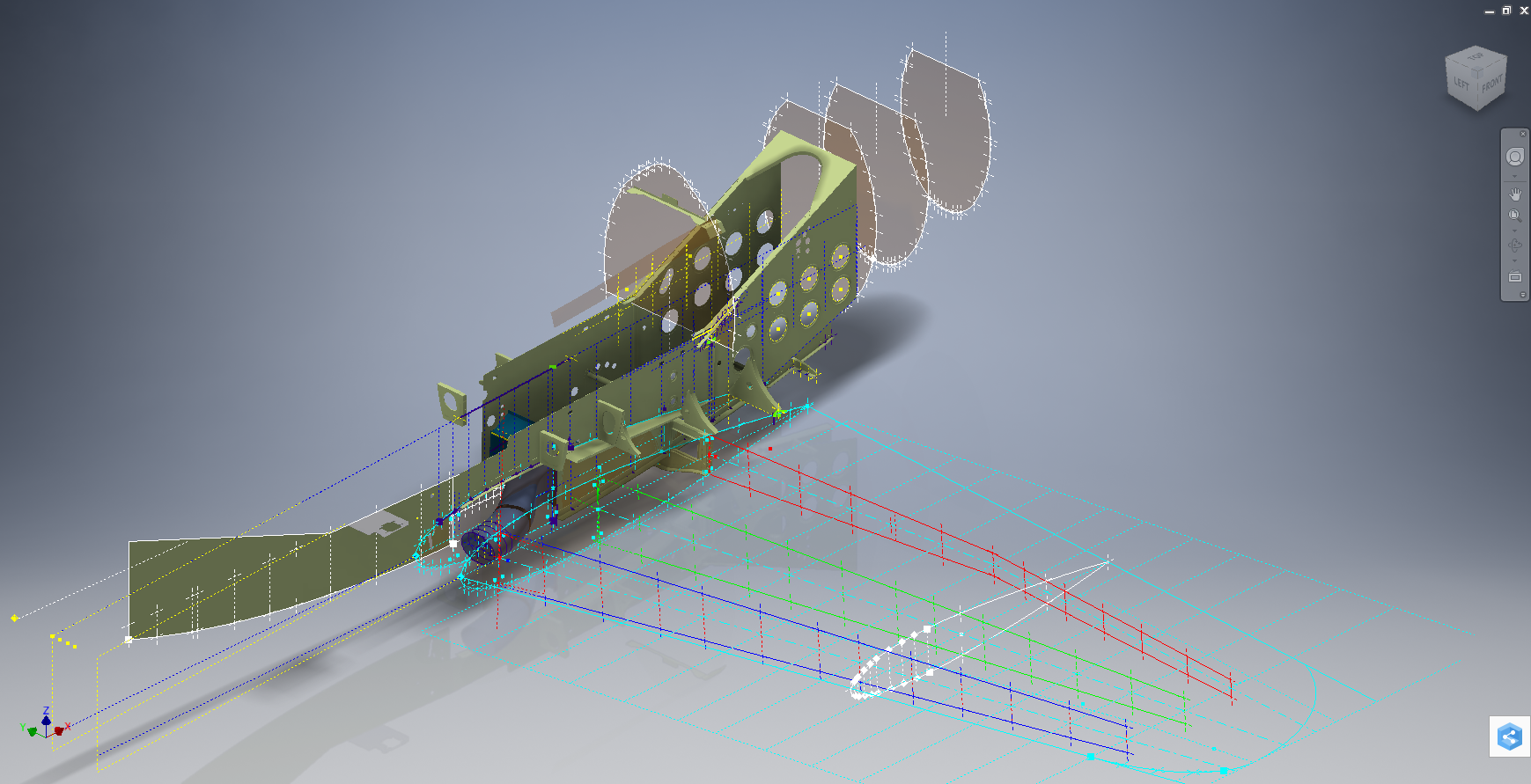

This is the lower level fuselage cross member that has a built in twist to align with the connecting frames at both ends. The model consists of 3 profiles with the 2 outer ones containing a small angular deviation in the centre at point A. Normally I would loft the profiles to create the finished surface but this projects the deviation throughout the length giving us 2 surfaces; which does not look good.

This is the lower level fuselage cross member that has a built in twist to align with the connecting frames at both ends. The model consists of 3 profiles with the 2 outer ones containing a small angular deviation in the centre at point A. Normally I would loft the profiles to create the finished surface but this projects the deviation throughout the length giving us 2 surfaces; which does not look good.