Technote: Inventor LT Bill of Material.

I normally use Inventor Professional but recently I decided to have a look at a common issue with Autodesk Inventor LT which is a part only product. Essentially the “lite” version of Inventor with limited functionality that excludes sheet metal, vba, ilogic, assembly mode and Bill of Material!. Technically the BOM capability is not a function of Inventor LT which I suspect is due to the fact it has no assembly environment but there is a workaround.

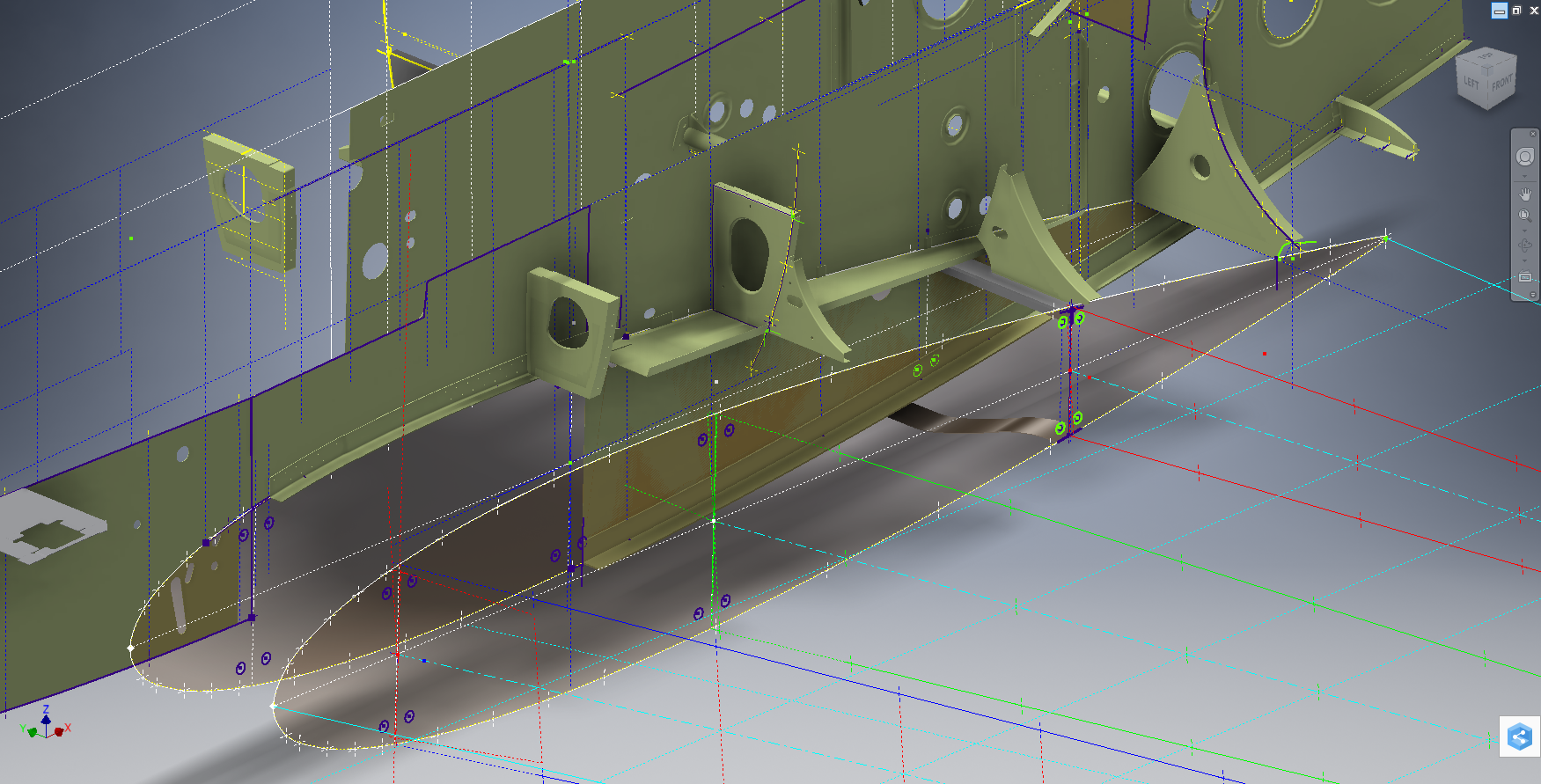

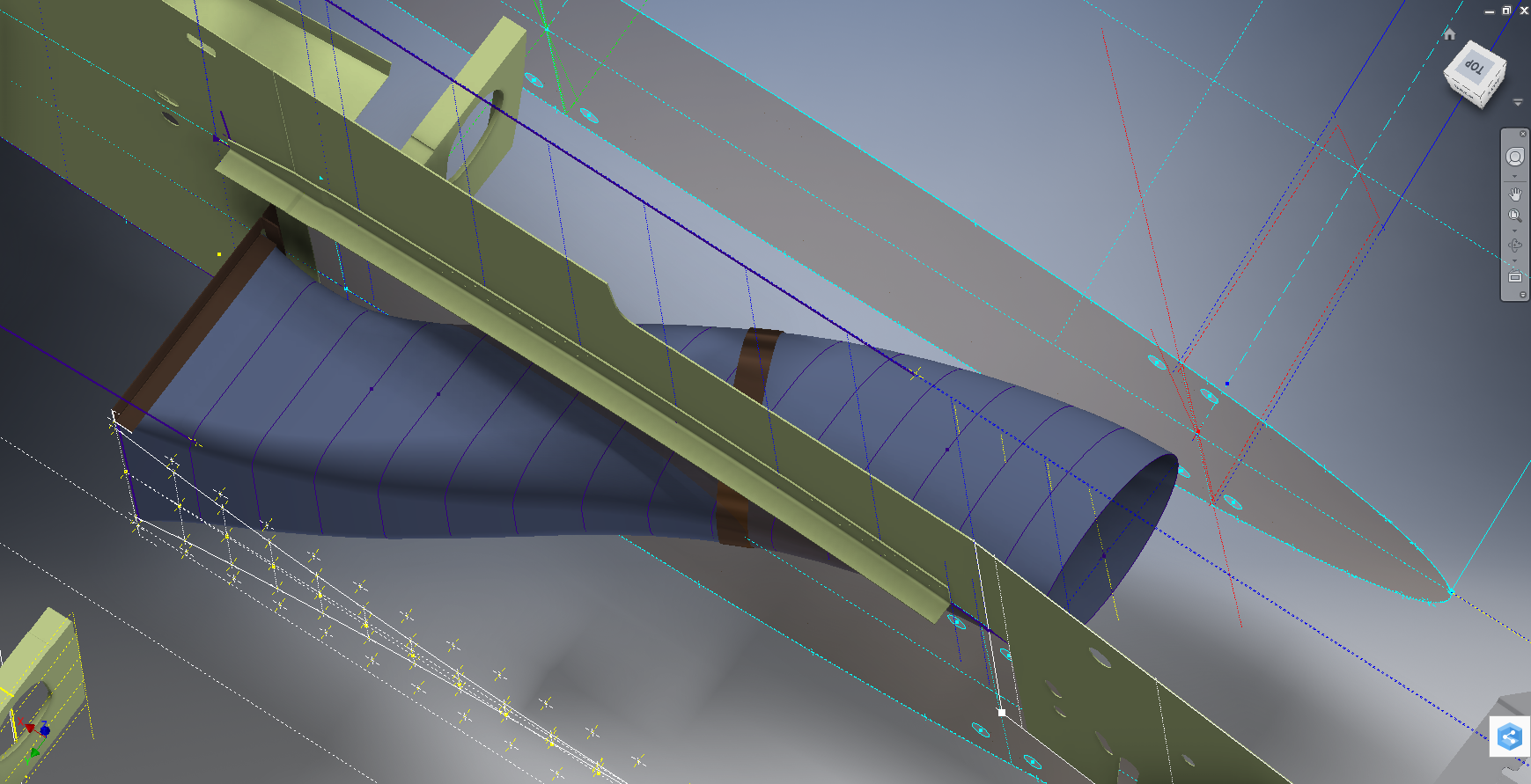

I should note that Inventor LT is a very capable modeling product which is ideal if you are mainly developing parts and if you do require an assembly environment to check the alignment of mating parts then you can use the derived function as explored in a previous post to assess this.

Whilst the product may be limited it does have a lot of functionality that can be exploited to overcome some of the limitations and the BOM is just one example of a situation that the forums, in general, described as something that cannot be done!

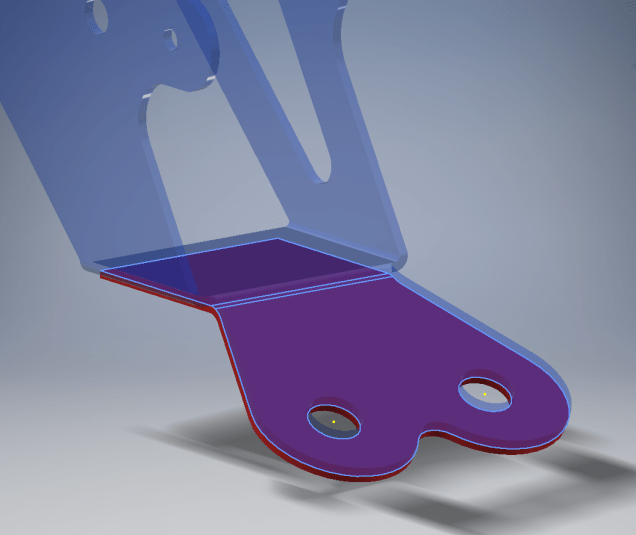

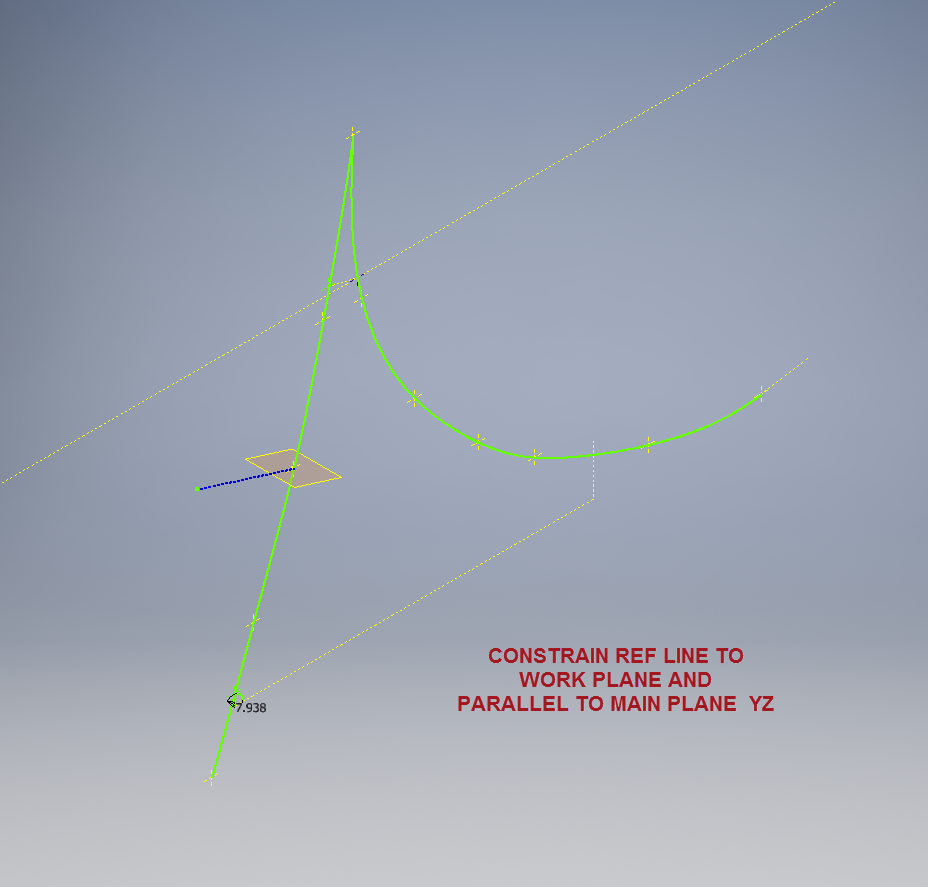

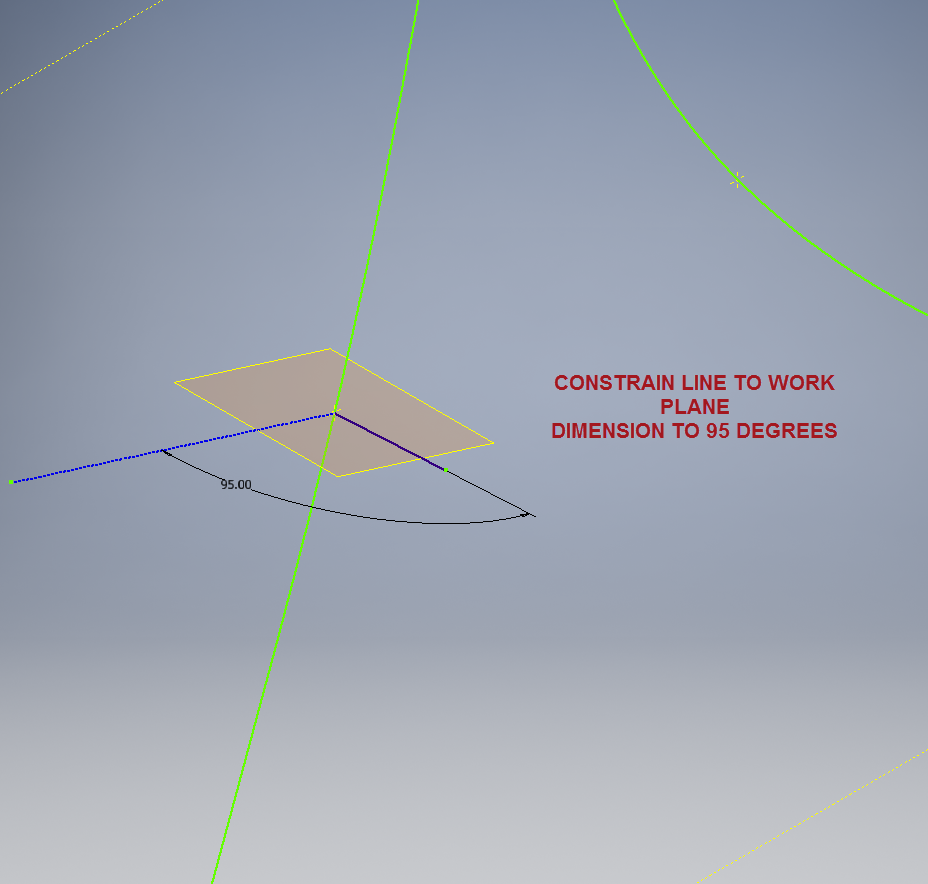

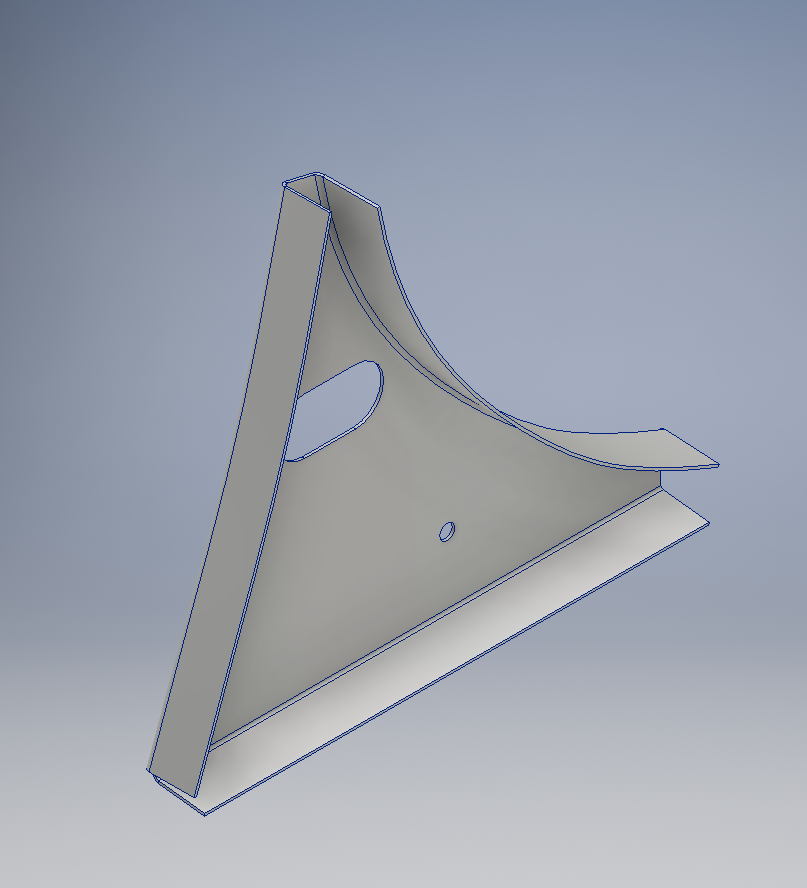

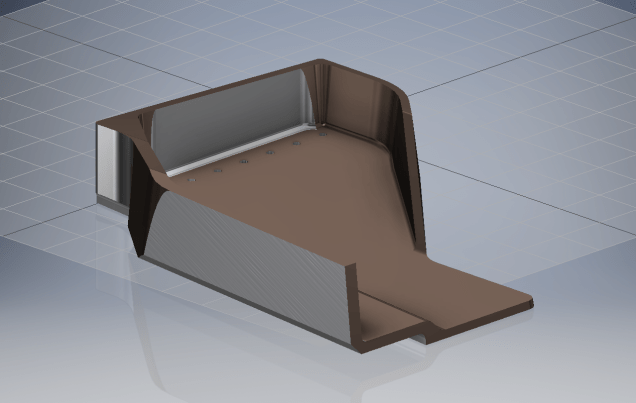

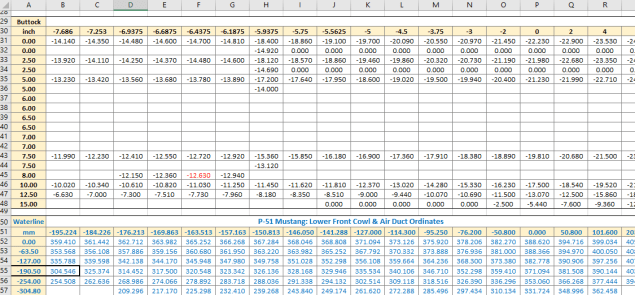

For this example we will continue with one of the parts from the previous article: the Bell P-39 Airacobra Centre Bulkhead fixing bracket.

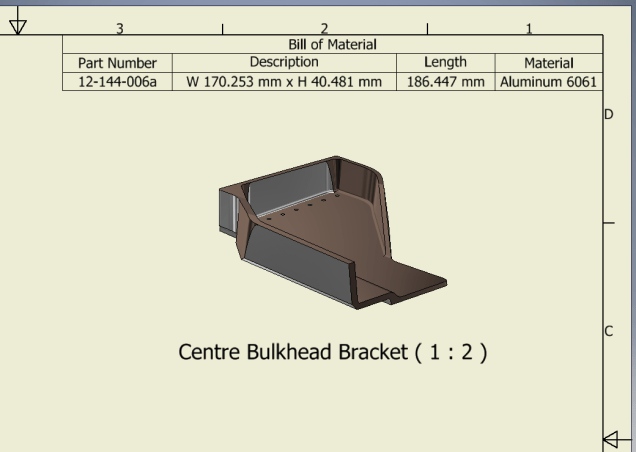

What I wish to do is have this part fully dimensioned on a drawing that also contains a basic table of properties that may be useful to the chap responsible for buying the raw material. Okay, I accept that the following image is not fully dimensioned but my primary interest is the generation of the BOM.

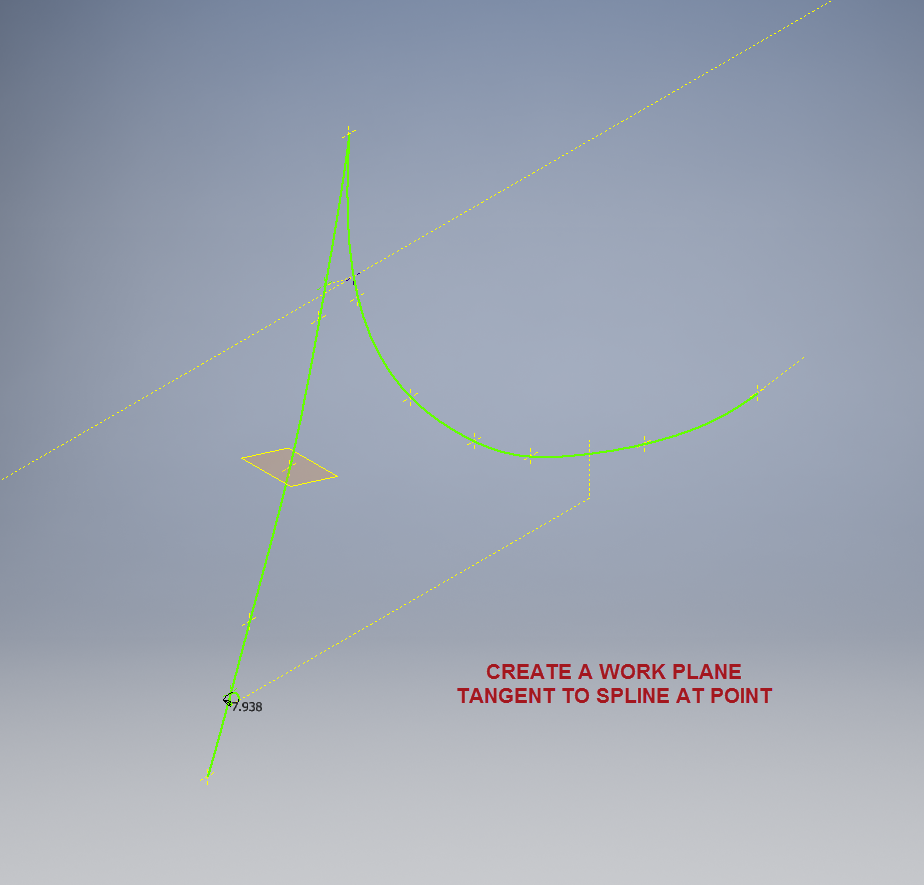

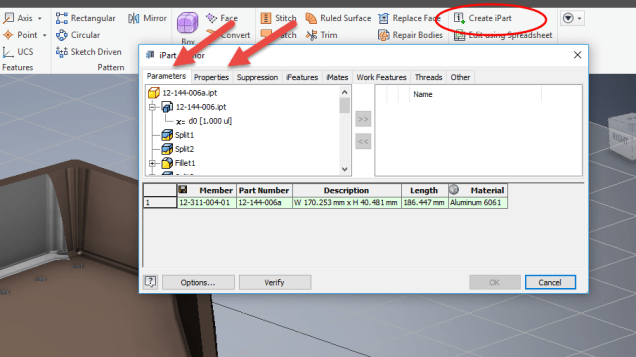

Inventor LT like its bigger brother contains a lot of part data which is accessible via the iProperties and Parameters, which we will utilize by using the iPart feature.

Normally iParts are used where a single part may come in varying sizes or configurations that share the same basic features; for example bolts! In this case we are creating only one version of the part. By adopting the capabilities of iParts we will create a table of selected data within the part file that we will later use as a data source for our BOM.

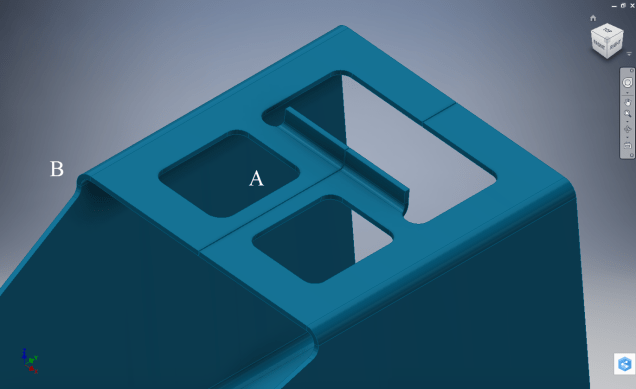

I won’t go into the technicalities of creating an iPart, there are many online resources that go into this in detail. Generally speaking, when creating an iPart you have access to all available data including parameters, model hierarchy data, and iProperties as shown above and it is simply a case of selecting the data you want.

This creates a Table which appears in the model browser. It is usually a good idea to give parameters meaningful names as I have done here for the Length, Width and Height.

This creates a Table which appears in the model browser. It is usually a good idea to give parameters meaningful names as I have done here for the Length, Width and Height.

The Description values are from the iProperties whereas the Length value is from the parameters.

This table can be further edited within Inventor LT or externally as an excel spreadsheet.

In the drawing environment, you select the General table option, Select View and then Column Chooser, add required columns, select OK and insert the table into your drawing.

…and there we have it…a BOM in an Inventor LT part drawing.

Part Quantities:

I have not mentioned part quantities which of course would be a prerequisite for any purchasing decision. You can, of course, create a parameter in the model file for quantity and include that in the table, but if this part serves a number of different assemblies then the quantity will vary accordingly.

Given a typical scenario where you are the manufacturer of components working collaboratively with other companies on a project how do you track quantities when you are using LT and the other guys are using Inventor and building assemblies.? You could, of course, just phone them or email them but as production schedules are critical you need a way of immediate notification of quantity changes.

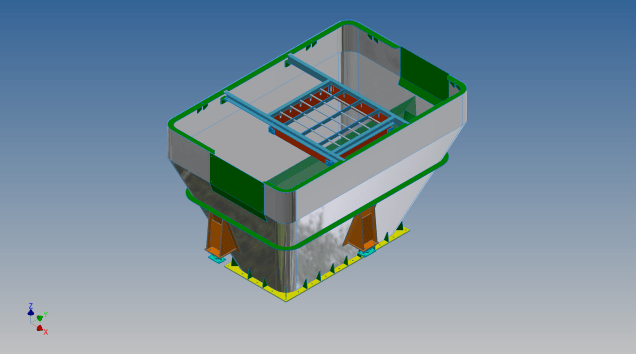

I faced a similar dilemma when I developed a modular solution for a power distribution company for design of sub stations. This resulted in vastly reducing the design time by over 60% which meant the procurement chaps had to up their game to keep on top of things.

Modular Approach to Sub-Station Design

The solution gave access to all project material BOMs without needing to bother engineers to create structured BOM extractions.

Briefly what we had was a top level assembly BOM which was interrogated by a custom database application to read the Part Name column and then search a folder of extracted cad model BOMs with the matching name and multiplying the quantity column in the part BOM with that of the assembly.

For example, the database would open the top level database above, read the columns Name & Descr (to be sure we were only looking for modules) and then import the corresponding data files with those names into the database. In this case, we only have 1 quantity per part, but that could be anything and the associated part file would be multiplied accordingly.

This is a very basic overview of what was done and beyond the scope of this blog to describe in detail. We have already demonstrated how to create and extract tables in LT and the main point here is though you may only have Inventor LT there are many options for creating data-sets in tables that can be shared and used productively in a collaborative environment.

Incidentally, the database I created was another of those instances where something could not be done!

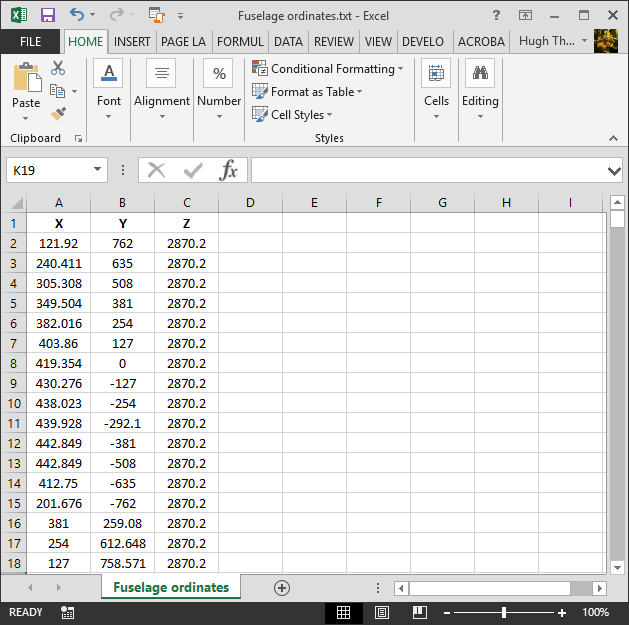

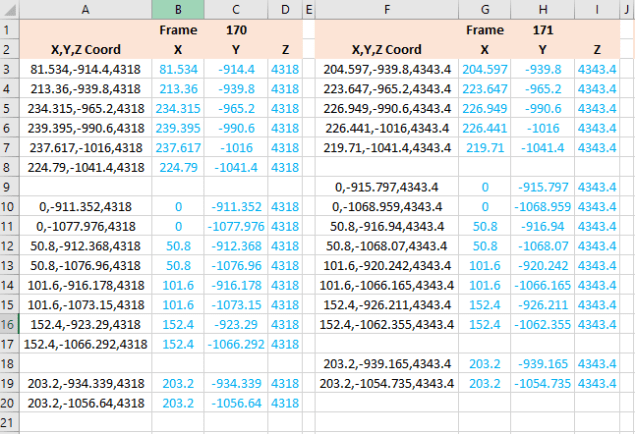

For use in Cad systems like Autocad, it is recommended to collate these in a TXT file by simply copying and pasting.

For use in Cad systems like Autocad, it is recommended to collate these in a TXT file by simply copying and pasting.