Technote: P-38 Forged Parts

I had promised an article on the P-38 Flap CAD development as a follow-up to my earlier article on this topic…but I deviated slightly to address a question from a reader about Forged Parts.

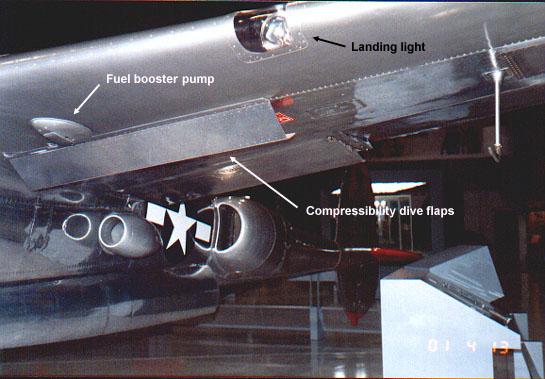

Typically for all these aircraft Forged parts are the main element in the process of manufacturing complex parts that may be used in such applications as Landing Gear. Such is the case with the P-38 Lightning where we have the main support members that are machined forged parts.

I have touched on this briefly in previous posts: Technote P-39 Inventor Face draft and P-51d Mustang Tailwheel Down Position support. Those articles tend to focus on using the Face draft feature in Inventor and using Derived model parts to differentiate between model states i.e. Forged and machined. I should note that with the later versions of Inventor, it is possible to contain the various Model states in one part file but I prefer to use separate derived Part files. The reason is that they are in fact 2 very different manufacturing processes and the drawings for each model may be sent to different departments or indeed different companies. So it makes sense to keep them separate.

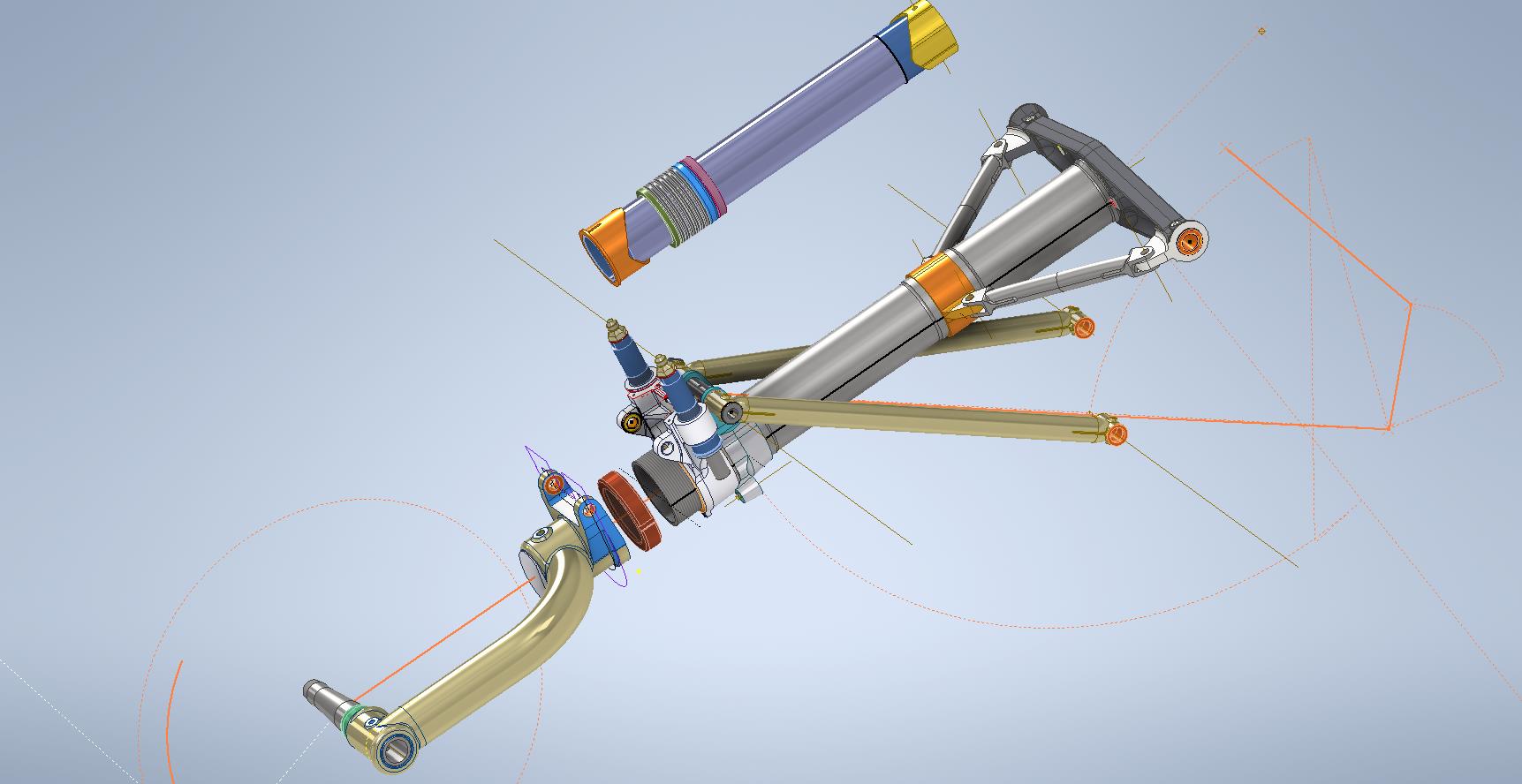

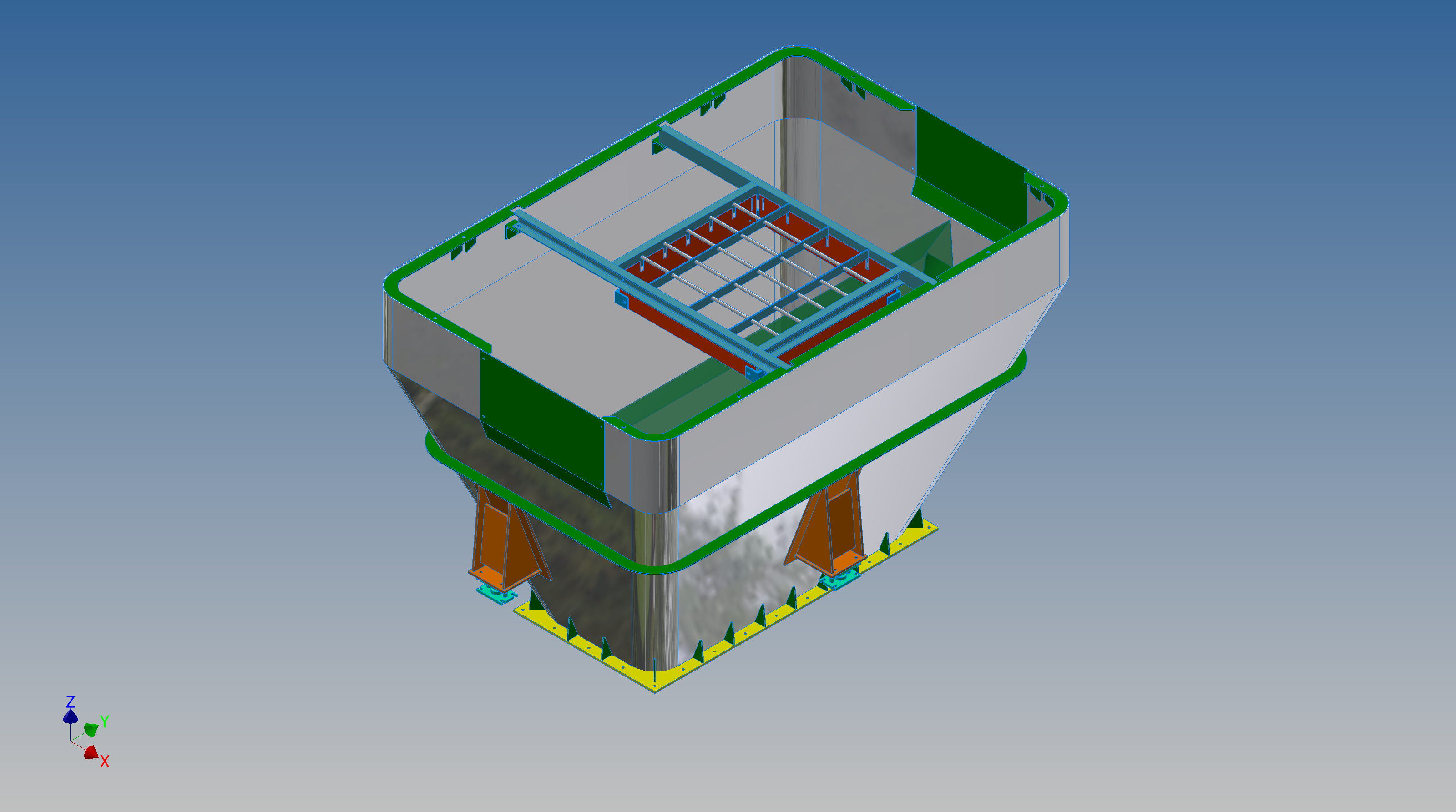

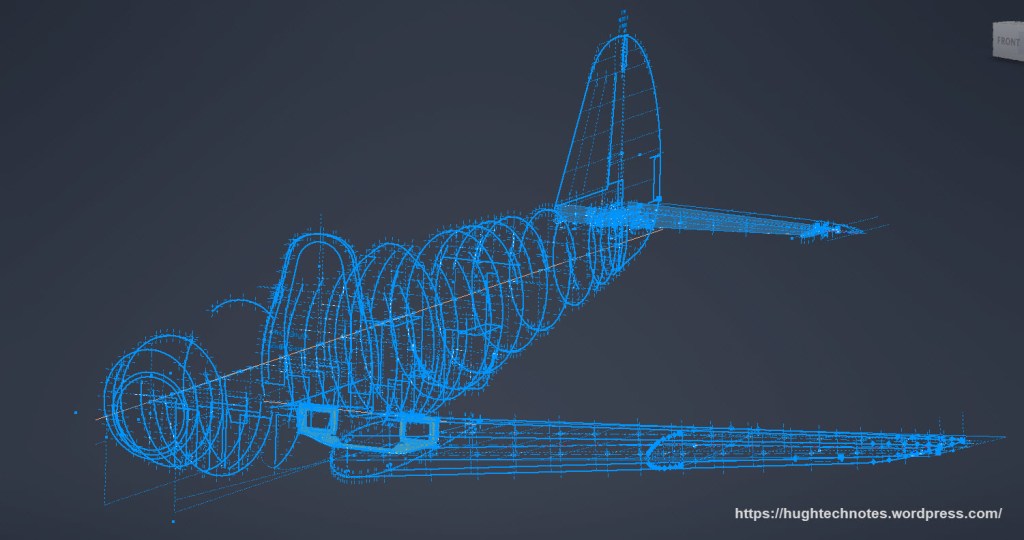

In the example above we have 2 components for the Main Landing Gear and the Nose Landing Gear. Both examples use the derived parts process as you can see. In this article, I wanted to cover some of the frustrating differences that you will likely encounter when building these models.

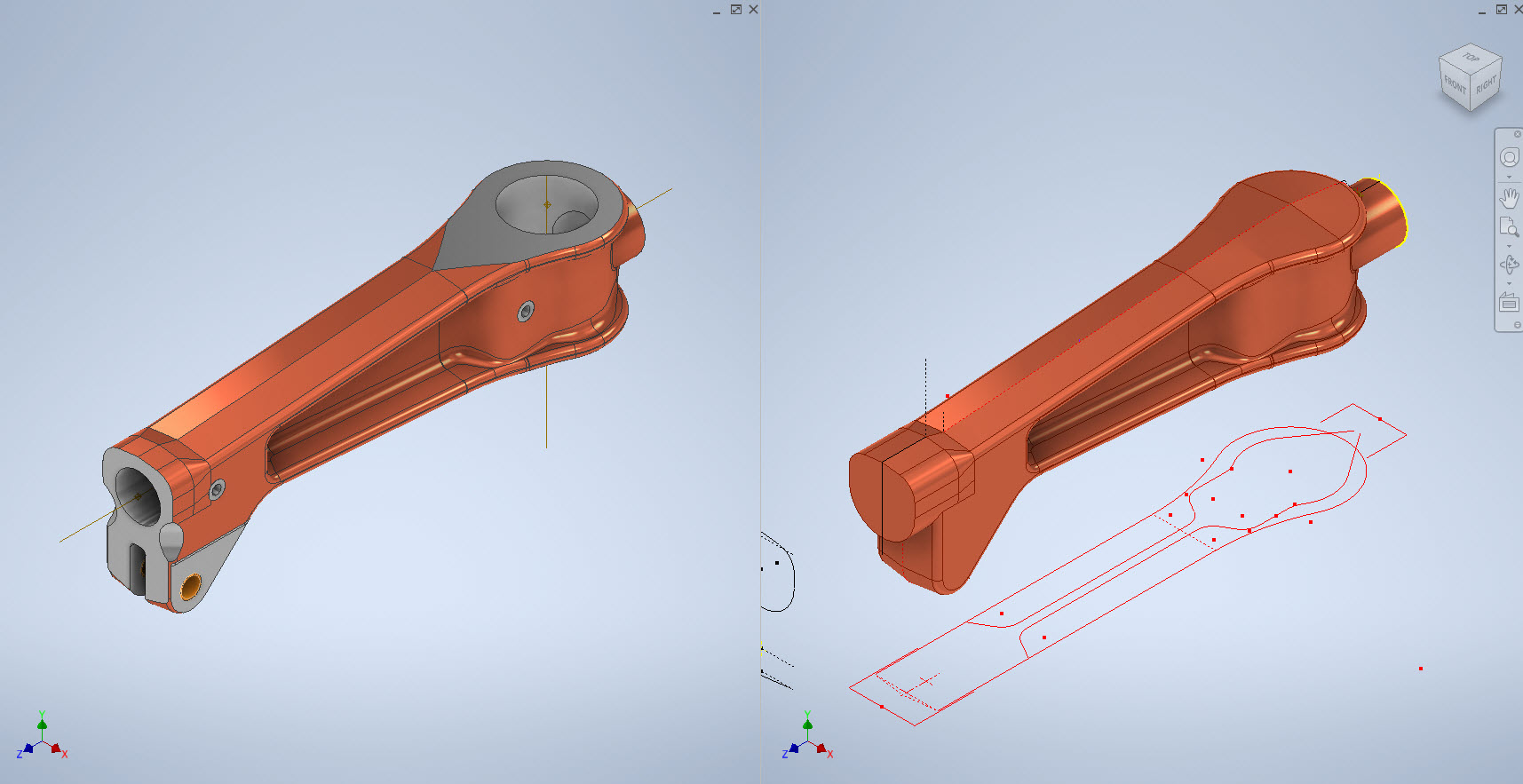

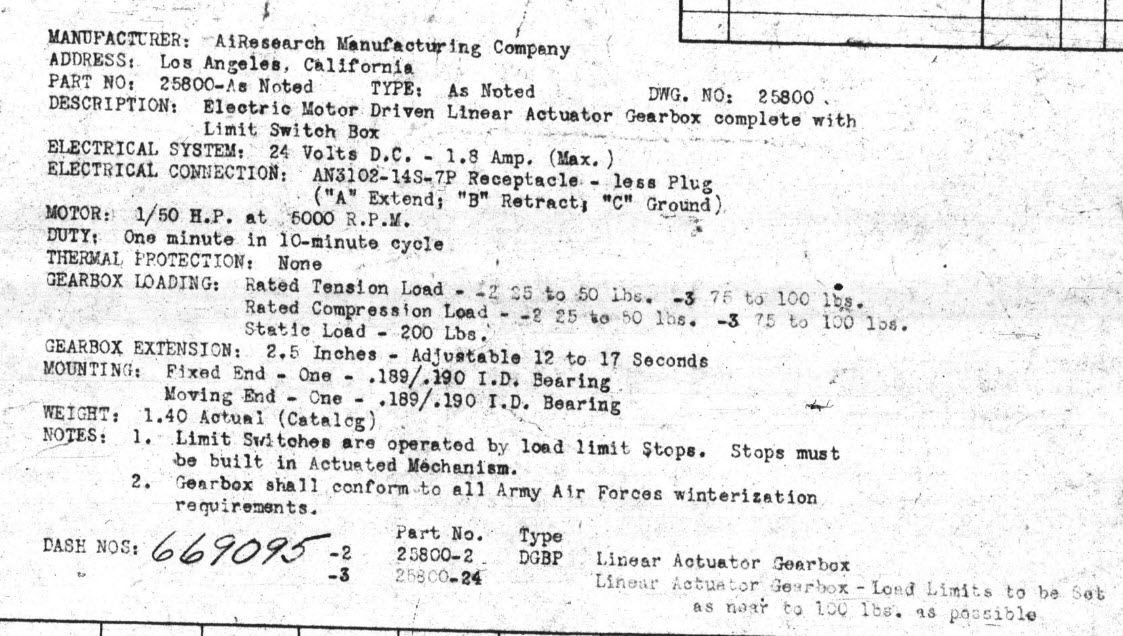

Forged Parts are notoriously complex and the Lockheed drawings tend to only provide the main dimensions and key elements often omitting small details that are likely to have been decided by the mold maker. To determine missing details I often build the models as a surface and then turn that into a final solid.

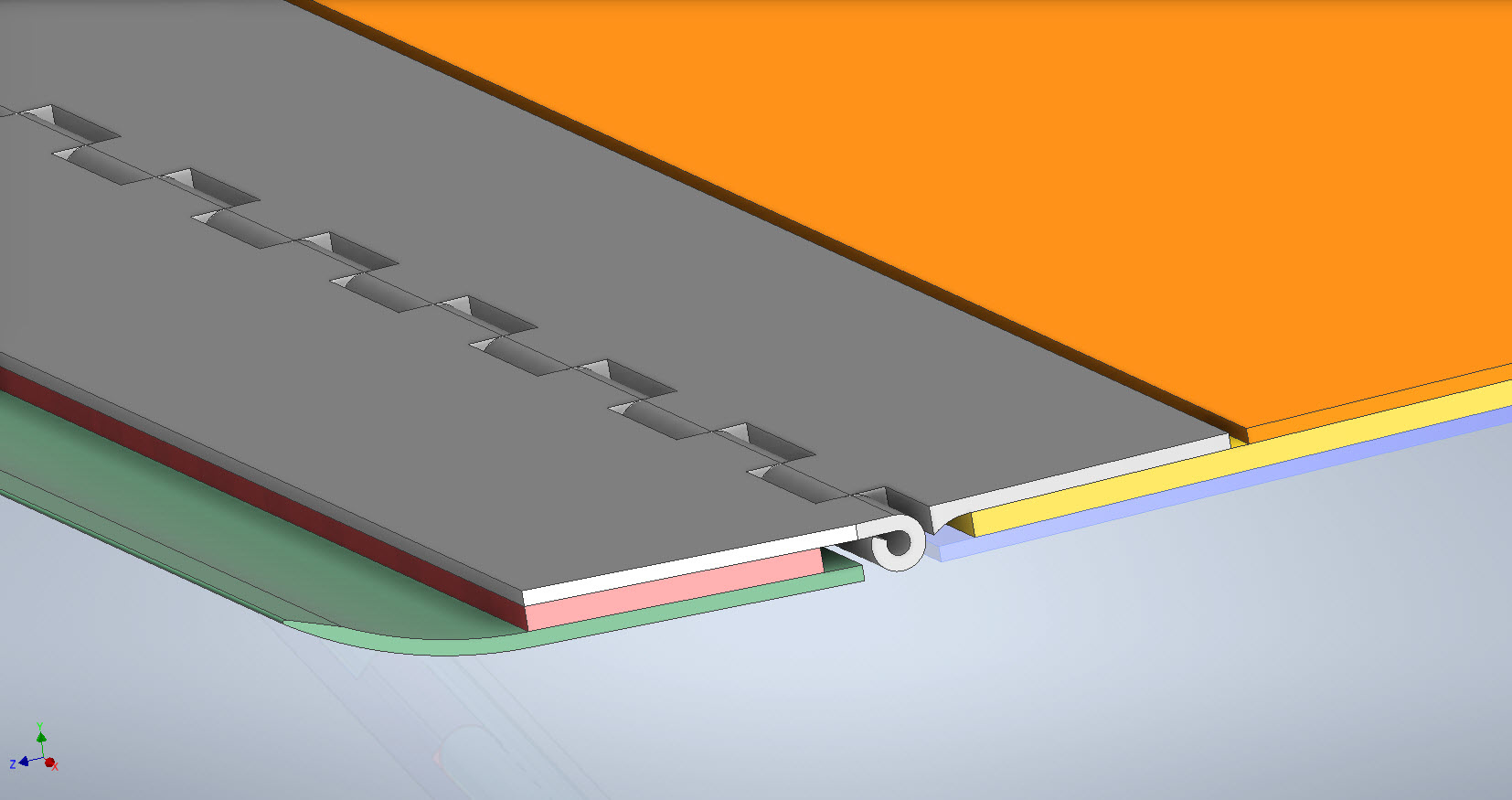

In the above images, this part had an elevated top and bottom section interspersed with a waveform for the main body. The 2d sketches were drawn outside the main part body to make it easier to visualize and manipulate the part data. This part used 3d intersection curves to generate a sweep path for the top and bottom profiles and the surface trim command to profile the main body.

Incidentally, although the sketches do not share the same space as the main model you can still select a single line from any of the sketches in order to trim parts and surfaces in the model…they do not need to be connected. I have often seen folks extrude surfaces from external sketches and then trimmings to that surface but you don’t have to do that…just select the line.

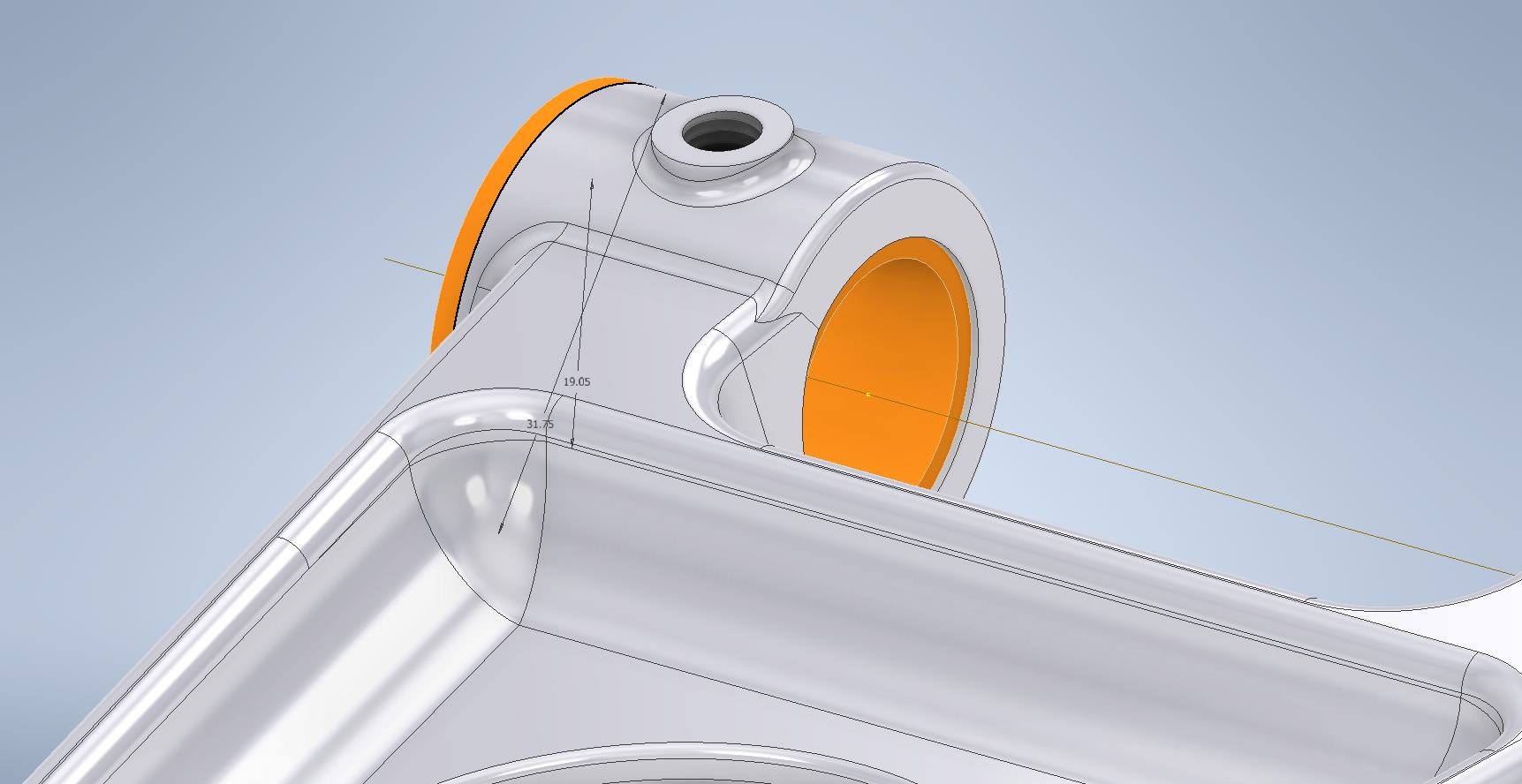

One of the key details that is not clear in this particular example was the protrusion just above the cylinder at the front of the model. All you have on the drawings is a line on elevation and 2 lines on the plan sketches..the specific details of how this small detail interfaces with the main body is down to interpretation. I modeled it with the flat upper surfaces tangent to the curved edge and applied a fillet to the intersecting sides. I did look at a number of variations but I think the end product is close to how it will actually be. This is the frustrating bit when trying to decipher designer intent with limited information.

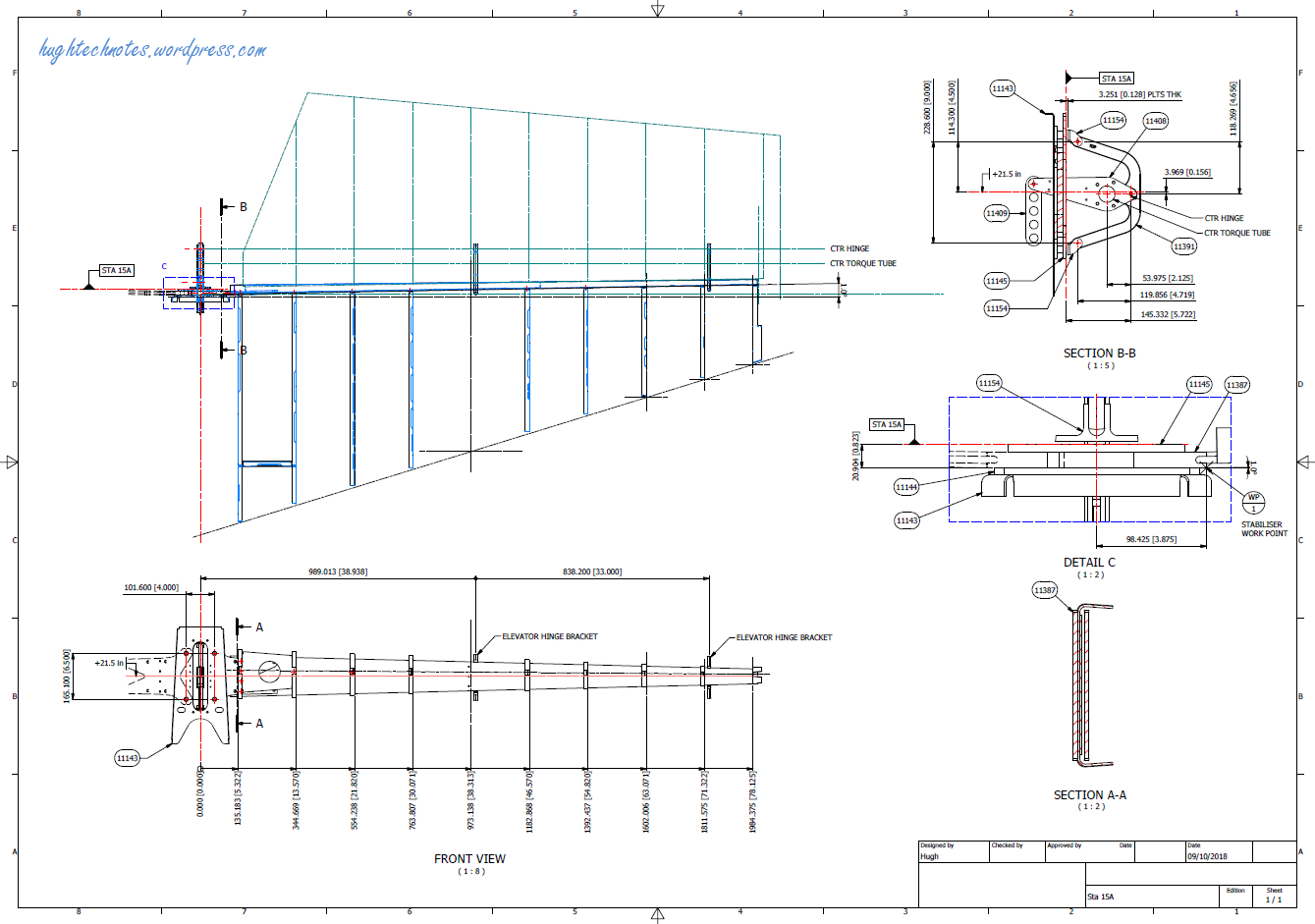

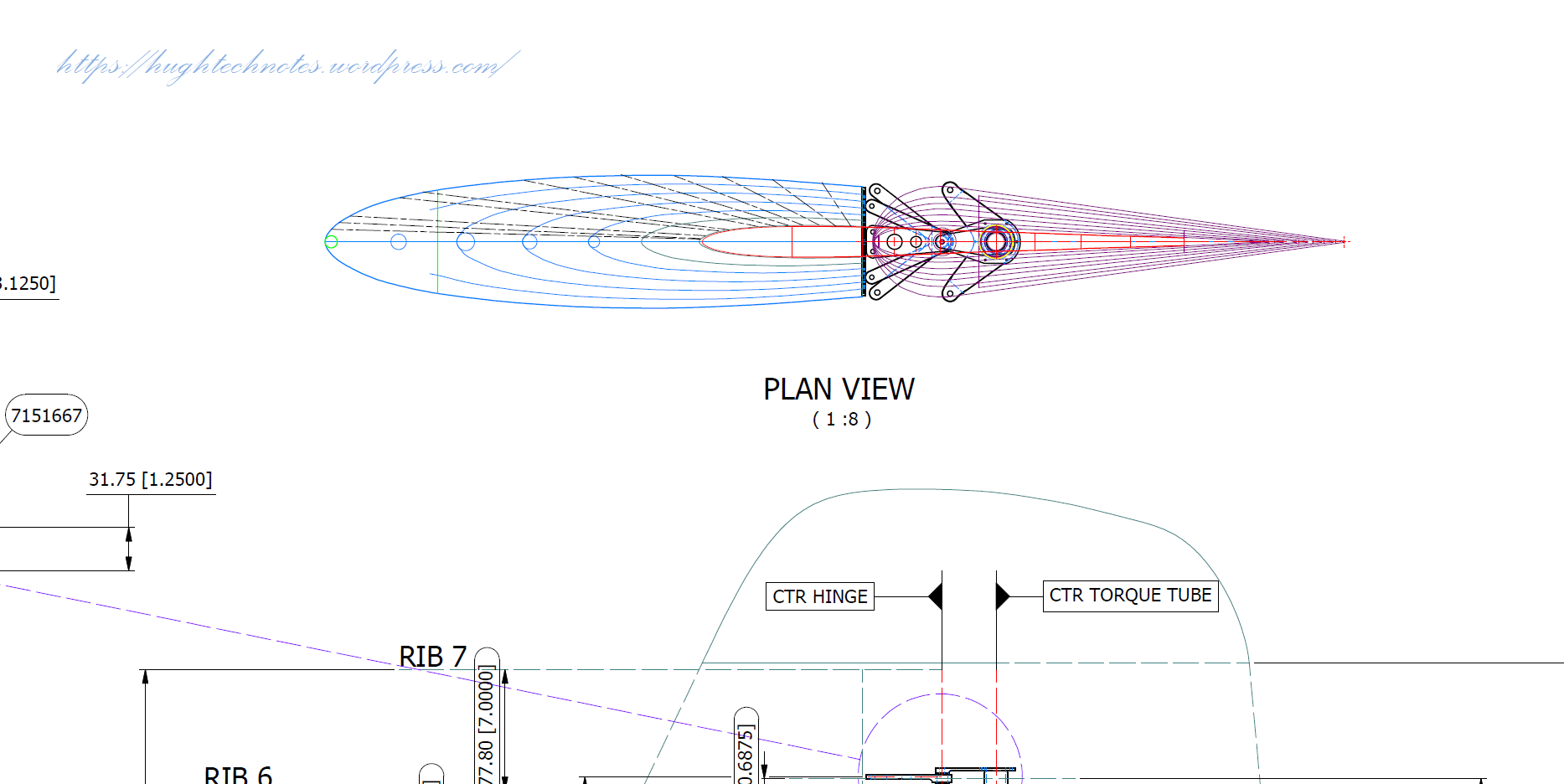

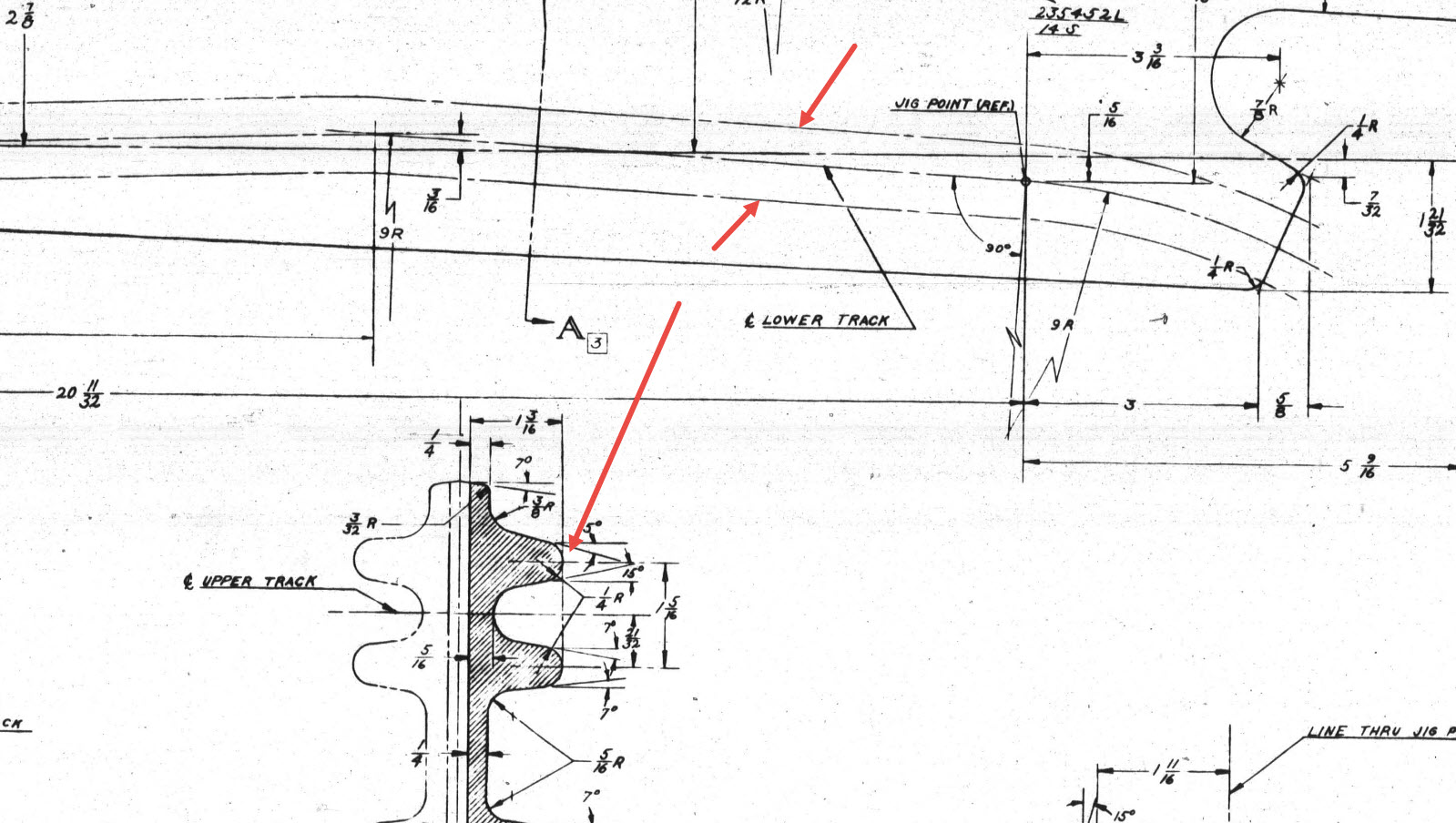

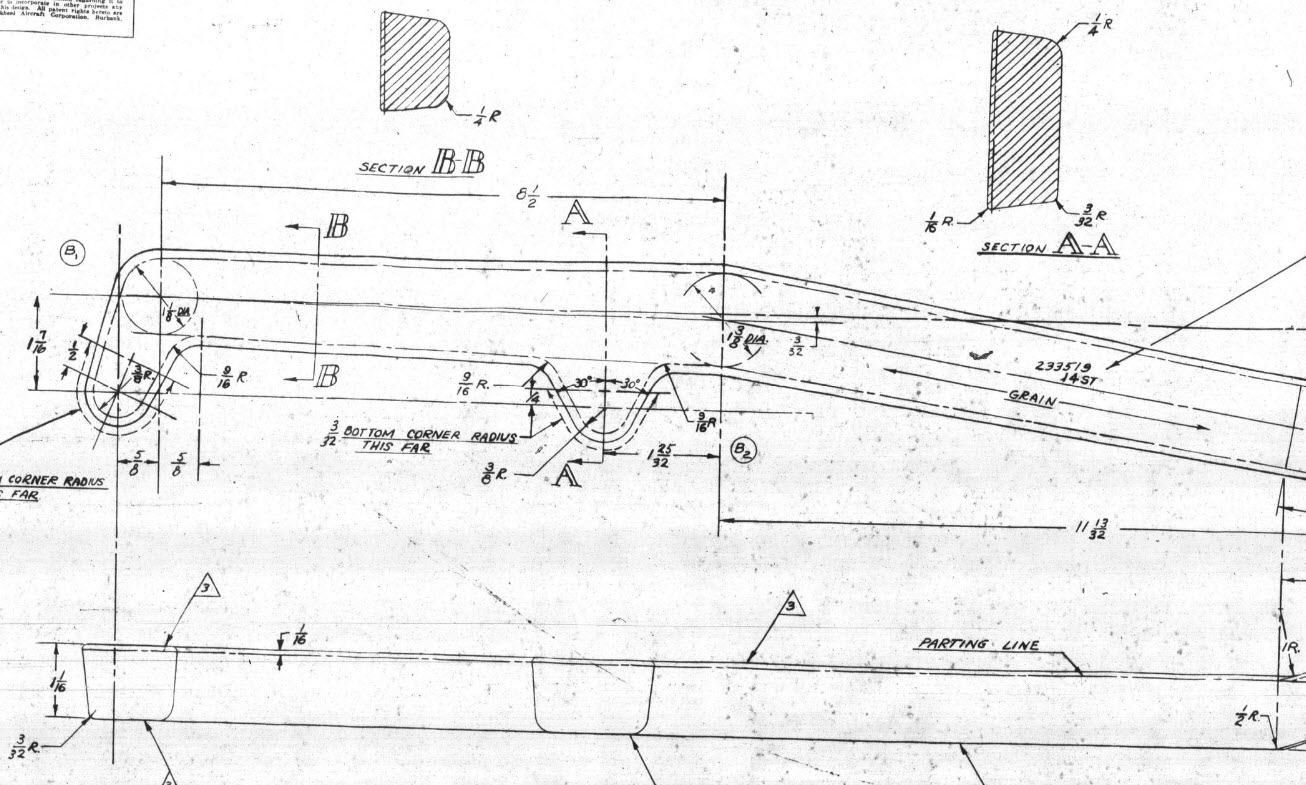

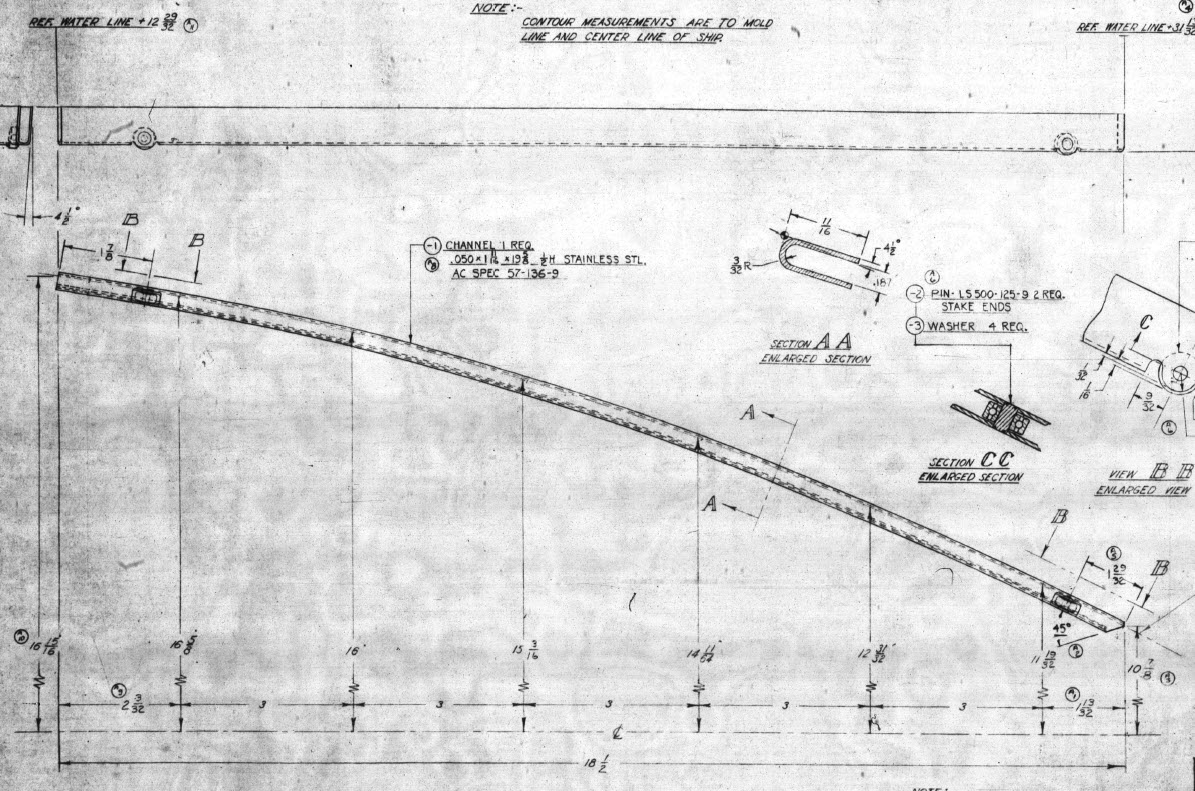

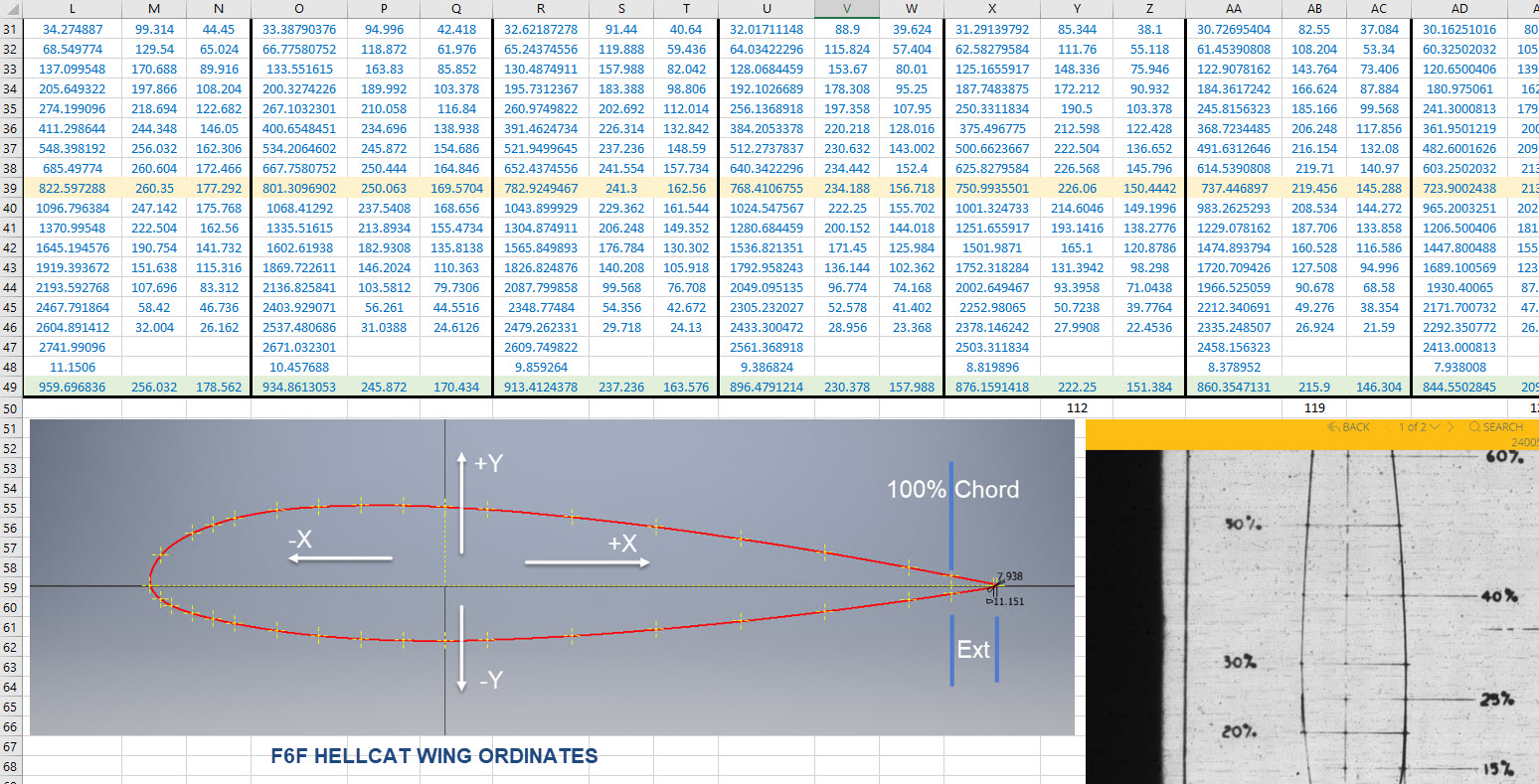

Some of the complexity comes from how the drawings themselves depict the dimensions of the profiled sections. In the first image above we have the criteria shown as the center line of the section’s curved profile. The second image shows a different part however this time the dimensions are to the projected edge intersection of the curved profile. The third image is also similar where the dimensions shown are to the projected intersections. The final image is the Flap carriage arm with the dimensions shown to a dotted line which is not clearly defined on either the sections or the main views to determine what this actually is. After much deliberation, I deiced to interpolate this line as the projected intersection of the drafted sides with the top and bottom faces. I had initially suspected this was to the corner tangent but that would entail a very complex development process due to the varying corner radius.

As you look through the dozens of forged part drawing there are all sorts of variations on the theme with few consistencies. This is where you can spend a lot of time determining how these dimensions relate to the model and how best to incorporate this information in such a manner to keep the model as simple as possible. Consequently, it is not unusual to spend upwards of between 3 and 4 hours modeling the forged parts. I think for the most part where doubt exists to work to a projected intersection as the point of dimension…it will be a lot easier to model and saves a whole lot of frustration.

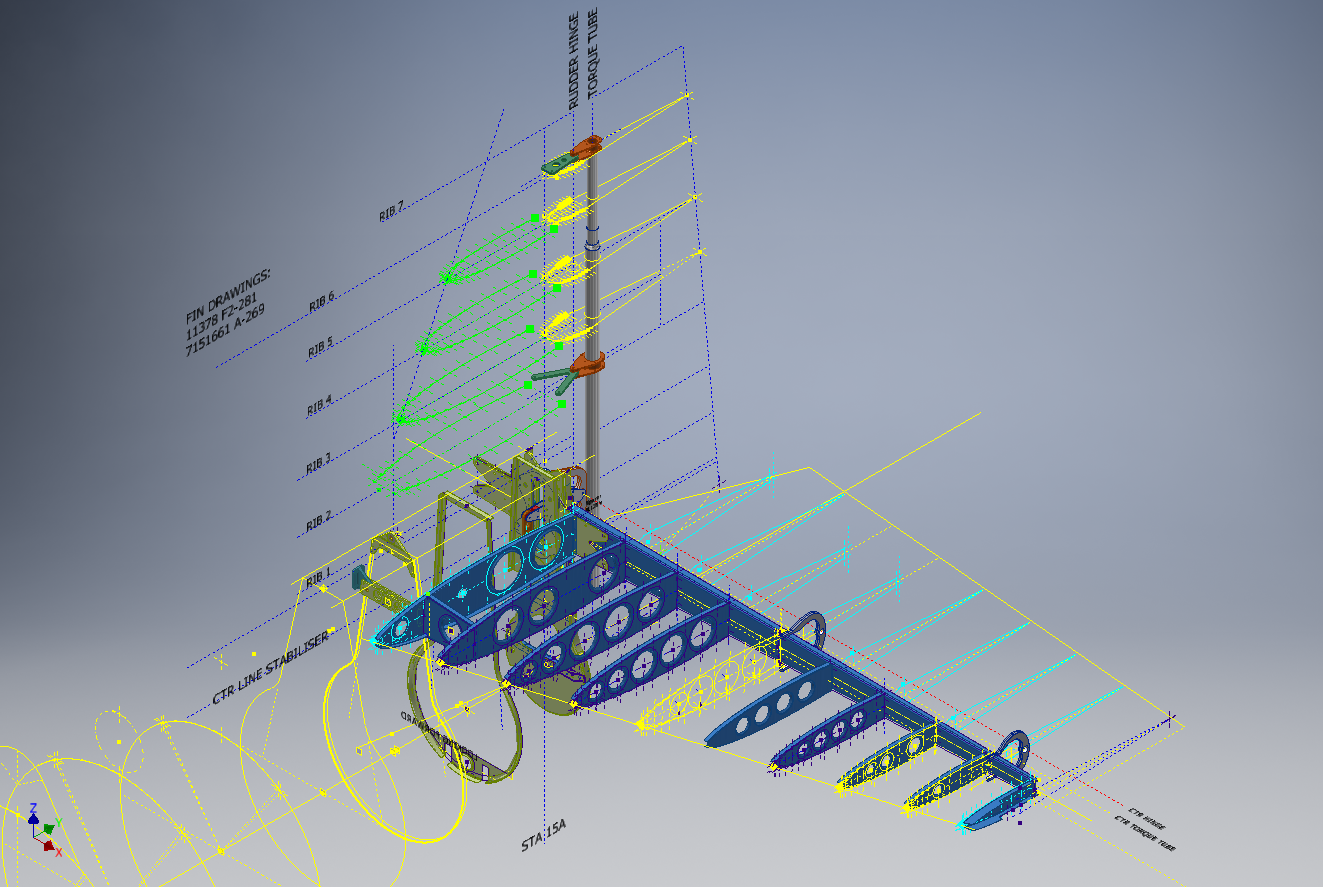

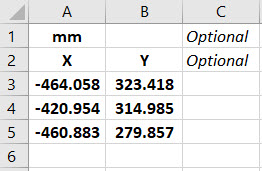

To give you some idea of progress on the Nose Landing Gear models:

In the latter 2 images, you may notice small differences which relate to the various model variances. I am modeling the P-38H and the comparison photo is the P-38J.

TechTip: Variable Fillets:

When modeling these complex parts often applying fillets can yield unexpected and undesirable results.

In the images above you can see how applying just standard fillets of different radii can result in quite an undesirable intersection between the flat plane and the circular node. What we need is continuity to achieve a smooth transition from one edge to the next as shown in the second image above. This can be achieved by using the Variable fillet feature.

Variable Fillets give us the option to vary the radius of the applied fillet. When you first apply the Variable Fillet you have a radius specified for the beginning and the end of the selection…you can apply additional points anywhere along the length of the selection to which we can adjust the radius at those points.

You can also add selection sets of edges to the original selection which have their own capacity for separate adjustment. To achieve our goal here for fillet continuity I have 4 selections: the top planar edge (1), the node circumference (2), the lower planar edge (4), and the remaining node circumference (3). It is important for each selection set fillet to have the same radius at each intersection to ensure continuity.

Each selection set is listed separately in the dialogue box and the way to adjust them is to simply select the edge selection as I have highlighted with the first one…this shows the applied points and values in the area below under the heading “Variable Fillet Behaviour”. I have added additional points to the planar fillets at 1 and 4 where the value is set to 2mm which then defines the radius between those 2 points. A small point worth noting is the diagonal draft parting line on the face of the round node that prevents selection continuity which is why we have 4 selections and not just one continuous.

It does not take long to do this and the end result is much more agreeable.

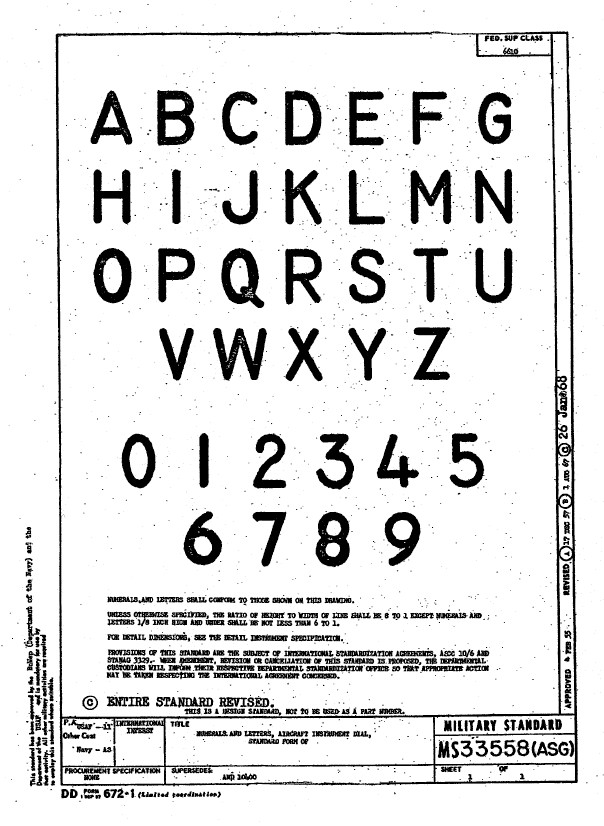

Using this font in CAD systems will result in problems with embossing or extruding.

Using this font in CAD systems will result in problems with embossing or extruding.