Technote: Steel Coke Plant: Using Regression Analysis:

Slightly off-topic this may be of interest to those working in the Steel Industry, particularly Coke Oven Plant machinery. I worked in this industry for a few years before being made redundant when the company closed operations.

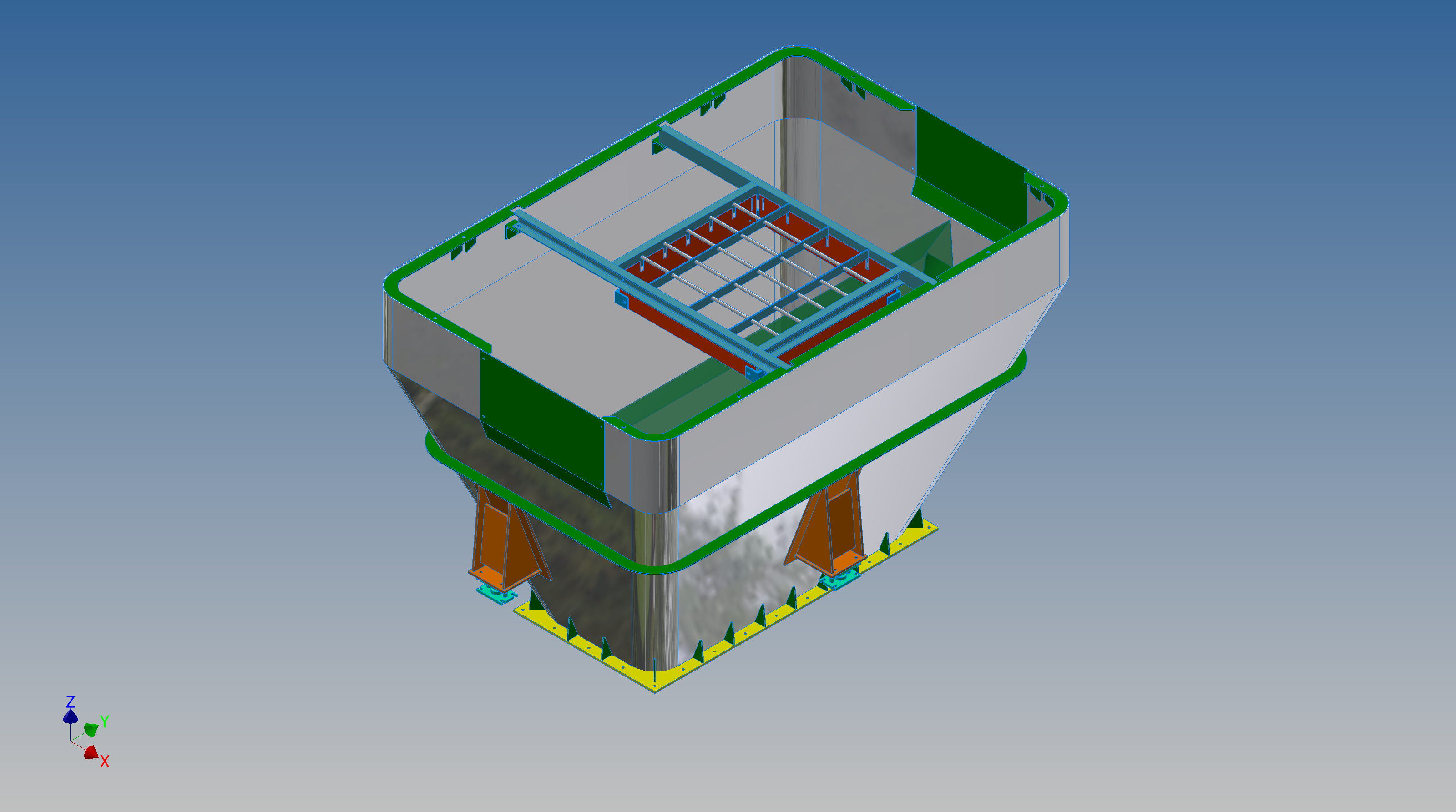

I briefly touched on the Application of surface modelling for tanks and hoppers to ensure volume and mass calculations are correctly interpreted in the CAD model. A link to that article is here. https://hughtechnotes.wordpress.com/2016/12/08/hoppers-surface-model-for-mass-containment/

This company for some reason were unaware of this technique which is one of the reasons why I wrote that blog article as others may also find it useful. An exert from the article:

“This type of hopper is fed from an overhead bunker and releases the fill material through an aperture in the base. The mass volume is modelled according to industry specifications that define the slope of the poured coal defined by the size of the top bunker opening.

The surface represents the containment boundary which has zero volume and zero mass therefore by definition will ensure that the only properties recorded for mass and volume in the 3d model relate only to the fill material.”

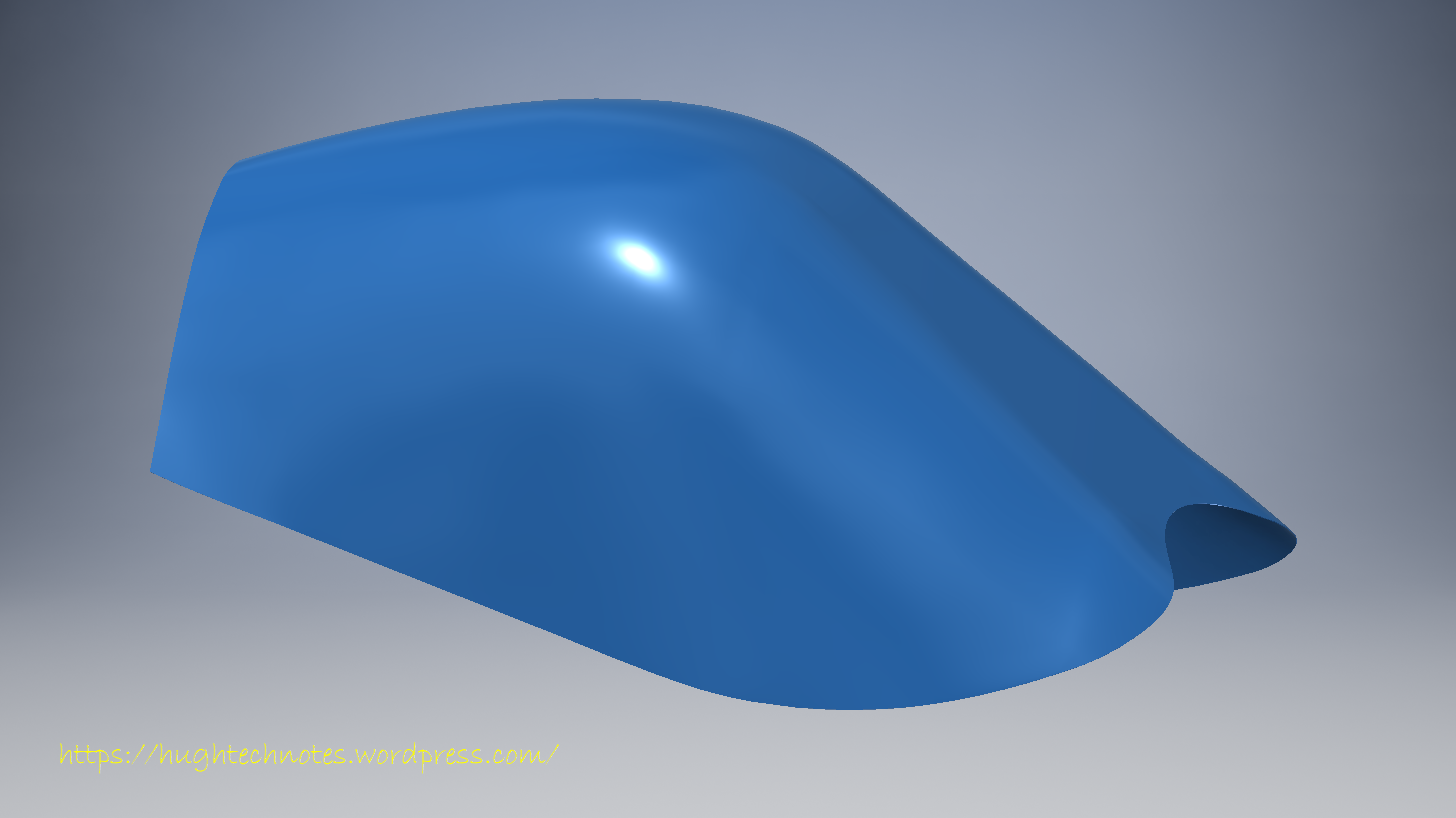

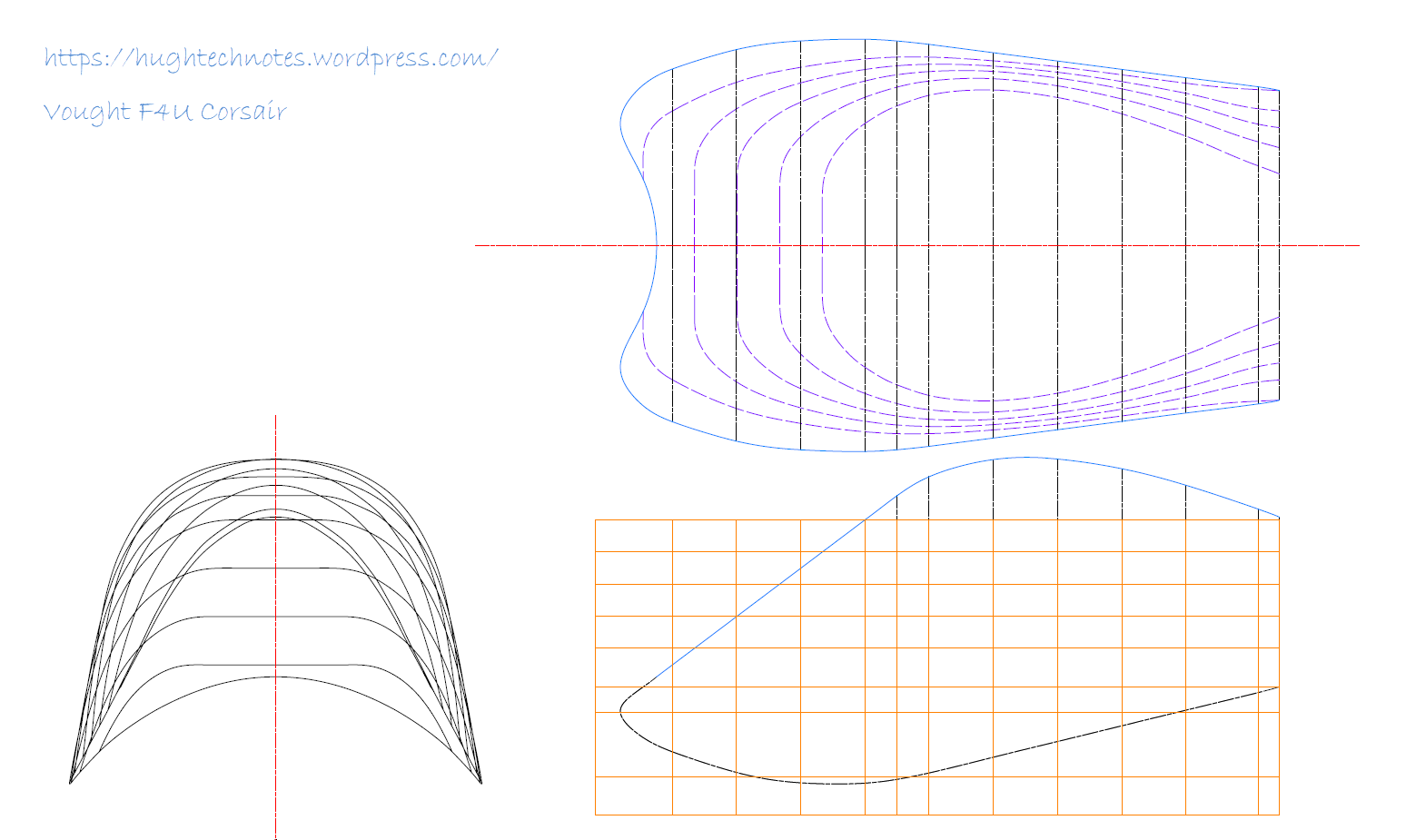

The type of machinery used to service Coke Ovens is extraordinarily large and heavy; that runs on rails not too dissimilar to trains. These images show examples of Transfer Cars that essentially transfer coal stored in overhead bunkers to the ovens below.

These machines work in a very corrosive environment and are often replaced with new vehicles after many years of service. A prerequisite to designing is to commission a fully detailed survey of the track rails and surrounding constructions, which provides the basic criteria and envelope parameters to define the design’s physical restrictions.

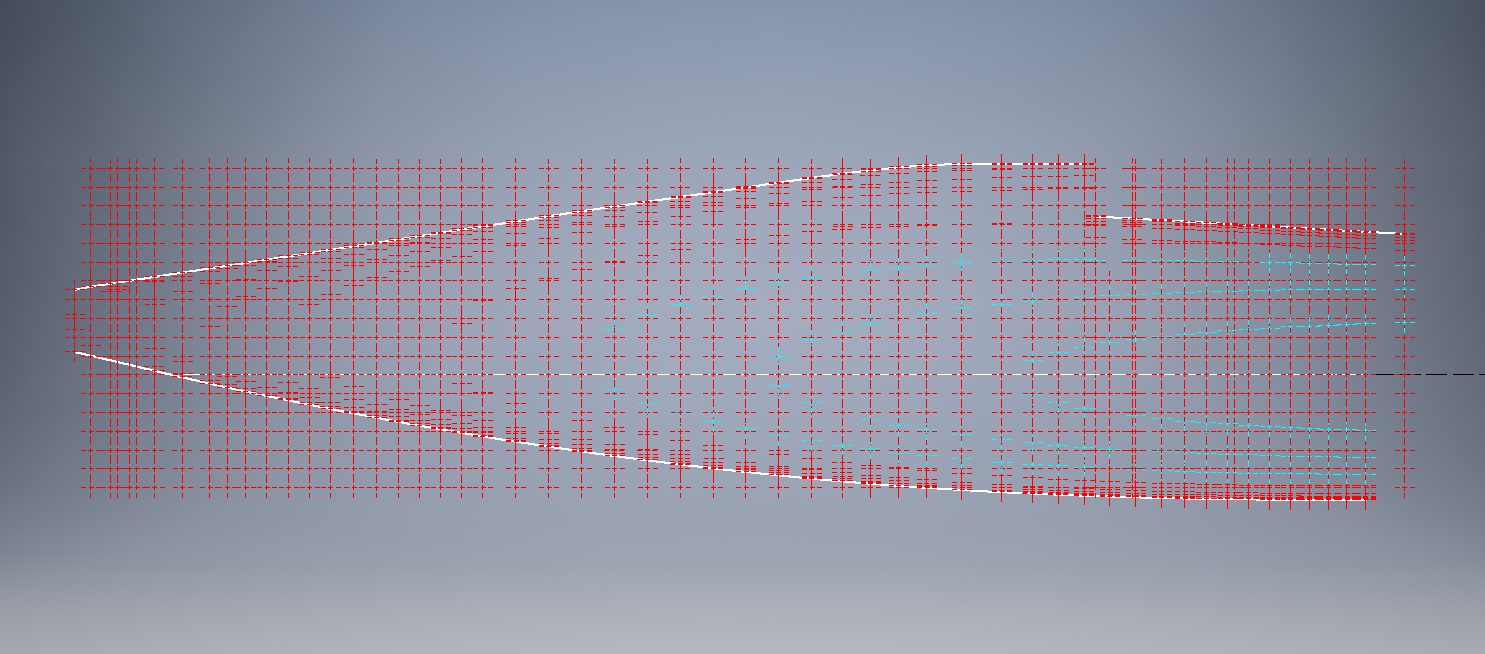

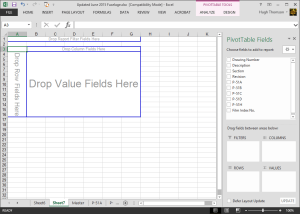

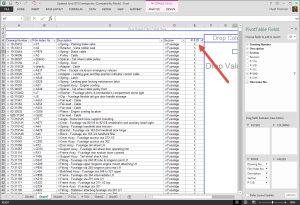

In this article what I am talking about is related to the rails on which these vehicles will run. As you can imagine after decades of use they tend to shift alignment and are never truly straight and in line. So it is important to have these correctly surveyed in order to determine the ideal location for the wheel centres on the bogeys. Before I started with this company the way this was done was simply to average out the survey information to achieve a suitable centre line on which to locate the wheels. I figured there may be a better way, so I introduced them to Linear Regression Analysis, which essentially does the same thing but more accurately.

Oddly enough the array of points shown in this Linear Regression Analysis is very similar to a survey plot of rails. It, therefore, was a logical progression to utilize this same technique to determine the Best Fit Centre Line for the Coke Oven machinery wheels.

I did this for a number of projects in each case establishing the linear regression for both tracks and in turn defining a line equation from which to extrapolate the ideal centre line. Because the 2 tracks were separate components the line equations would be slightly different with both rails not necessarily being parallel at any given point. So what happens next is to essentially repeat the process this time finding the ideal best fit line between the tracks and then checking in CAD to see how the vehicle would run.

I termed this process as Crabbing, essentially checking the determined centre of the vehicle and therefore the wheel centres along the length of the Liner regression track lines. There is obviously some adaptability built into the bogey designs to account for track variation and it is the purpose of this exercise to determine whether we could achieve movement of the vehicle within the requisite design parameters.

This is also a technique that can be used to optimise ordinate profiles where accuracy is critical. When you think about it most dimensional data points are specified to an accuracy of 1/32″ or 0.7mm which is normally within acceptable parameters however for greater accuracy why not try using linear regression analysis?

It was a useful technique and worked very well. So next time you need to determine the best fit line within a range of static survey points perhaps consider using Linear Regression to help achieve the desired results.

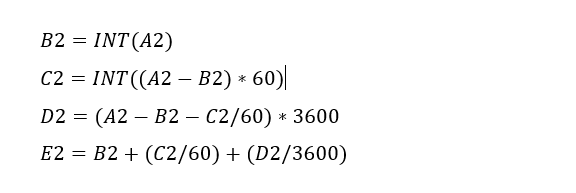

The original formula for one of the constants “P” is given as shown (1). If we enter the formula as prescribed in a hand calculator it will evaluate correctly but will not work correctly in Excel in this format. So we need to tell Excel to essentially divide everything in the top line by everything in the bottom by adding parenthesis as shown (2).

The original formula for one of the constants “P” is given as shown (1). If we enter the formula as prescribed in a hand calculator it will evaluate correctly but will not work correctly in Excel in this format. So we need to tell Excel to essentially divide everything in the top line by everything in the bottom by adding parenthesis as shown (2).